By William A., Mei C. special thanks to Dennis Rovere for his valuable insights and corrections

Martial arts in general and Chinese martial arts in particular have been characterized by an aura of mystery on what a devoted practitioner can achieve after mastering a traditional style. Many of these misconceptions stemmed from novels, movies and in a great degree from the Chinese originators themselves who have created myths to sale their product to the unsuspected masses looking to for a way to protect themselves or achieve other personal goals. The appearance of MMA, social media outlets like You Tube and martial arts Travelodge series such as Kung Fu Quest, Fight Quest, Human Weapon, Mind Body and Kick Ass Moves has helped bring further scrutiny to the claims of many about how effective their systems really are.

The attentive person will notice when routines/taolu applications are demonstrated most often than not it is against a smaller person, always in a cooperative setting and if rarely applied with resistance the techniques do not resemble the original moves contained in taolu sequences. Some reasons for such discrepancies are rooted in the broken transmission of a system, either due to the originator/disciples never completed their training, a teacher unwillingness to pass on the entire curriculum, political/social events that cause the water down of many arts, skills that were never meant to be use in a real confrontation (flowery) etc. It is therefore up to those who want to preserve those traditions to reconstruct the lost elements; however this leads a system to become something entirely different from the original intent and the beginning of a new synthesis and with time a “traditional” style.

When I finally met Yang Chengfu and learned from him, I became aware that it was not the case that they did not teach people, but that unfortunately there had been those who partook of the teachings and then misrepresented them, making up lots of fraudulent tales which others heard and then made use of in the writing of novels. People with ulterior motives – are they not among the “kinds of people who should not be taught”?

… I had previously heard of General Li Fanchen [Jinglin], who is an expert in the sword art and had been taught by an exceptional man [Chen Shijun], when Sun Lutang happened to speak highly of him. Li came to Shanghai this year, so I went to see him. He is a brilliant and frank man, and was generous enough to teach me his two-person sparring method for the sword…

In Yang Chengfu’s curriculum, there are no standard two-person sparring exercises, so by obtaining this [supplementary training from Li Jinglin], the Taiji Sword would then be complete in terms of its function as well as its essence. Taiji Sword by Chen Weiming, 1928 (Brennan)

The above paragraph illustrates how a martial art loses practical elements and had to be reconstructed with other arts, yet this does not stop individuals from claiming to possess the secret transmission to distinguish themselves from the competition as martial arts have been and still are a source of revenue for many people. Much of the criticism about Chinese martial arts is aimed at their lack of practicality; however this has not always been the case as we will develop in this essay.

Republican Era Publications

In addition, transmission of ancestral techniques has been limited by the secret and the proliferation of different schools (pai). This is a shame, because of all these reasons; they have broken the guoshu body. To be able to disseminate guoshu in society, guoshu should be studied using scientific methods, open to the public in general, researching different systems and organizing them in a systematic way. Guoshu: Zhe Jiang Sheng Guoshu Guan Yue Kan, 1929

Despite the monumental effort by the Central National Arts Academy to bring to light the many styles that existed during the Republican period and to encourage the local population to practice Chinese martial arts, a quick survey using a sample population of sixty Republican era books illustrating styles such as Xingyiquan, Baguazhang, Taijiquan, Lienbuquan, Tantui, Liuhetantui, Bajiquan, Chinese martial arts discussions on history etc., a common issue arises. These manuals show the variety of the subjects covered at the time. As well, many of these books were also partially reproduced in Republican periodicals as a means to introduce them to the potential buyer. The manuals reviewed for the comparison, illustrated for the most part single and cooperative partner practice both armed and empty hand taolu/routine practice. However these exercises do not really teach how to apply the routines in real fighting when compared with the “how to do” martial arts books of recent years. From the above sample only 6% of the books surveyed had illustrations and explanations on actual practical usage as described below:

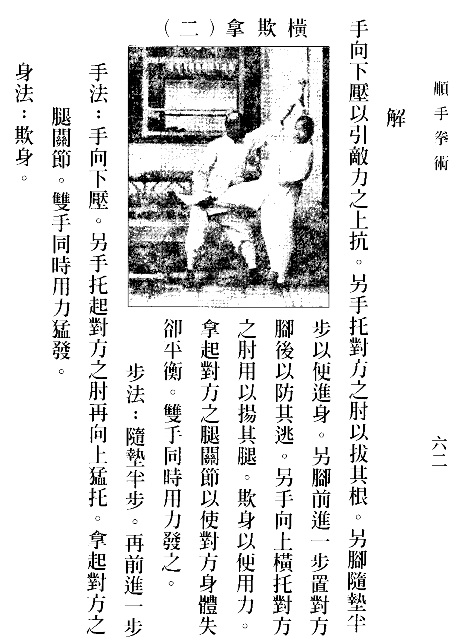

Shunshou Quanshu, Shun Hand Boxing by Huang Bao Ting. (Note: These are two manuals). These books are entirely different both in content and format published throughout 1934. They included Qin Na, throwing, knock downs and striking techniques illustrated in several photographs.

Shaolin Pobi, Shaolin Wall Breaking by Yan De Hua. The manual includes kicking, throwing and striking techniques with hand drawings illustrations, published in March 1936.

Zhongguo Shuaijiao Fa, Method of Chinese Wrestling by Tong Jun Zhi, published in September 1931

It is unquestionable the wealth of information contained in these books regarding what the authors thought of their arts and hints and how martial arts were practice, however unless the reader had previous experience with the specific art or the guidance of a competent teacher these publications were not very good sources for a beginner or even an intermediate student’s learning. This issue makes one wonder how willing the authors were to truly make Chinese martial arts accessible to the public in general and whether or not some of the authors knew how to apply them. Traditionally fighting applications are still considered a “close doors” activity reserved to a selected few, unlike modern Sanda/sanshou and even MMA where students learn fighting drills and applications from the start of their training. A situation that puts traditional Chinese martial arts at a disadvantage in today’s martial arts market.

The Importance of Open Competition

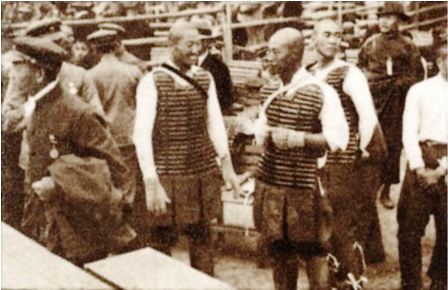

On April 21, 1923 the English press reported on a large Chinese martial arts competition held in Shanghai and sponsored by Ma Liang with the attendance of more than one thousand athletes from across China. The events included (Chinese) “boxing, wrestling, dancing, tumbling, expert sword, knife and dagger play”. The competition was also attended by members of the Jing Wu Association, members of the 47th mixed brigade of the 2nd Division of the Frontier Defense Army under the command of Ma Liang, among others. The description of the many demonstrations seems to indicate the only non cooperative/agonistic event was Chinese wrestling. This approach of mostly taolu/routines style competition would change in 1928. The wave of openness in the practice of Chinese martial arts during the Republican era was lead by both private and state sponsored organizations with the Central National Arts Academy (Zhongguo Guoshu Guan) as an example of the latter. One important initiative inspired by the ancient Military Examinations (Wu Ju, 武舉) was the institution of the National Examinations. This approach of combative events and how it would help revitalize Chinese martial arts is explained in the following statement by the Central National Arts Academy’s Magazine (Zhongyang Guoshu Guan Hui Kan) as an inward reflection of the state of Chinese martial arts and what these thinkers thought was a serious flaw when compared to other foreign nations’ approach to physical training:

Our nation has existed for more than 5000 years, unfortunately our culture is decreasing and our economy is in a very bad situation […] our nation has neglected physical training due to the lack of competition systems. This has been the reason for which these practices have been weakened. The impact of this situation has caused indirectly that our people have not come to the defense of our nation (Acevedo & Cheung, Republic Period Guoshu Periodicals, 2014)

The magazine also describes in general terms how national arts examinations were organized. The tests were divided into three levels, namely: national, provincial and local. Each level was organized by the Academy, with the national government setting the date for its realization. In the provincial exam, the national Government would inform the provincial government of the date for this test, similarly the provincial government would inform its local counterpart. Candidates had to be approved by two qualifiers in the local test. Once approved, the candidate would receive a certificate of recommendation that could be used for the provincial examination; similarly, the candidate had to go through a similar process in the provincial review and thus earn the right to attend the national exam.

The national guoshu exam included subjects such as: bouts of Chinese boxing (quan ke jiao), wrestling (shuai jiao ke) and weapons (qi xie ke). The latter event included spear (qian), staff (gun), knife (dao) and double-edged sword (jian). In theory the candidate had to pass the boxing, wrestling and one weapon events. On the national exam, it was mandatory to test in boxing and wrestling, and the candidates could choose one of the four weapons. The candidate was assessed not only for their knowledge of national studies, but also for their ethics. Secondly, the national examination included national studies (guo xue) which included: the three principles of the people (San min zhu yi), history of the National Arts, foundations of physiology and hygiene. In the local and provincial reviews the most important component was empty hand fighting against an opponent (dui shi quan jiao). The candidate had to pass boxing and one more of the remaining tests.

The tests had two parts, a preliminary examination (shi yu) and formal examination (zheng shi); failing the preliminary test disqualified the candidate. The National preliminary examination objective was to demonstrate skill in boxing and weapons via taolu demonstrations. The same process was followed in local and provincial exams (a requirement that was dropped for the second national exam in 1933). During the formal examination a lottery system was used to select the opponents in the described categories, assigned each candidate a number and the winners of their respective bouts were once more paired with another opponent following the same system. (Acevedo & Cheung, Republic Period Guoshu Periodicals, 2014). This work would be used later on as a template for the standardization of Chinese martial arts competition after the Liberation. Despite the emphasis on practical application martial arts had to be modified to make them safer for competition, including devising a set of regulations, protective gear, weight classes, study and analysis of techniques with higher percentage of success when applied etc (Acevedo & Cheung, Republic Period Guoshu Periodicals, 2014). It goes without saying that training at the academy required uncooperative practice e.g. wrestling and free fighting (Miller, 1992) in order to be prepared for the examination. Practices such as tui shou (push hands), two person taolu/routines are tools used to develop attributes prior to free fighting but cannot replaced sparring altogether.

Approximately eight years ago it was reported that footage of the examinations had been discovered and a private screening was allowed. Those who saw the material commented that the level of competition displayed was “mediocre” when compared with modern Sanda/Sanshou events. The footage was quickly censored and to date has not been released to the general public. Without seen the footage we can only make some educated guesses about the reasons of such results with a more recent example. The first UFC competitions in the early 1990s were “messy” affairs if one compares these fights with more recent ones. The early UFC as the republican Examinations were a field experiment on rules/regulations, protective gear, fighting techniques, training methodologies among others that unlike the UFC were hindered and even stopped altogether due to the Sino Japanese conflict, the civil war and other sociopolitical events that marked the early XXth century China. We can only guess how the Guoshu experiment could have been if allowed to develop and flourish.

As for how Sanshou training was approached at the academy we can use an example that has been transmitted until today in the form of a taolu sequence reported to have been created at the Central National Arts Academy. The routine in question was known as Youth Fist/Boxing, Qing Nian Quan a basic sequence practiced in a straight line moving forward in the first half and then retreating in the second half. Once the student was able to move smoothly, he/she would learn a simple punch sequence moving forward with a partner who would only perform a block against the opponents punch, the roles would then be changed always moving in a straight line. Once the partner exercise was mastered, the students would work in pairs with one performing the first half of the routine and the second student the second half and then the roles will be switched. As the students mastered the sequence, speed and power was added. The next step in the learning process would break the routine into smaller sequences of attack and defense in rapid succession. A more advanced exercise had the students performing the two person set moving in a circle. The last stage would concentrate in couple moves from the sequence and the individual applications will be practice against a partner at which point free sparring could be introduced (Lin W. , 2005). As the students learnt more routines their repertoire of techniques would grow further. At the Academy this traditional approach was followed along with the application of modern (at the time) training methodologies.

Western sports allow open discussion and share experiences. However our nation has remained closed; we envy the advances of others and hide our disadvantages. Who do we blame that our sports are declining? Our Martial Essence has become the reason for the advance of our boxing, combining Northern and Southern schools. There is no preference for any. Why don’t we try to expose the features of each school in an open manner to understand and correct their disadvantages? And in this way improve our traditional sports in a scientific and systematic way. Martial Essence Association Special Edition (Jingwu Te Kan) by the Shanghai’s Athletic Association of the Martial Essence, 1923 (Acevedo & Cheung, Republic Period Guoshu Periodicals, 2014)

At this point we have provided some information illustrating both a concern about the need for realism while at the same time what other individuals were doing by either removing and/or reserving the disclosure of those very important skills contained in the practice of Chinese martial arts from the general public during the Republican era. In part II we will review the methodology used in training China’s armed forces during the same time period and draw basic comparisons and conclusions from the given examples.

Reblogged this on Ground Dragon Martial Arts.

Very informative article. Thank you for also including the pronunciation of some of the Chinese words.

Glad you found it informative, cheers