Couple weeks ago, I had the chance to travel to Toronto for a few days and as I was preparing my trip, I thought I could squeeze in some training while in the city. I have been aware of the Big Spear (Da Qiang) training for a few years now after attending a competition in 2001 in Toronto. After registration the attendees had a short intro in the use of the spear and then went on to face the other competitors who came mainly from Canada and the US. After returning to Alberta I bought two wax wood long spears for practice, but did not use them as much in the years that followed. I was gladly surprise when couple years ago I found the Facebook group IDaqiang and decided I had to contact them to see if I could get some training while in the city. I received a very quick replay with the information where and what time to meet. This brief article introduces the work of Dr. James Guo Ph.D. (Guo Xiao Bo, 郭肖波) a martial arts scholar from Taiwan who was a student of famous Bajiquan master Liu Yun Qiao. With master Liu Dr. Guo learnt Bajiquan, Baguazhang, traditional weapons etc.

NOTE: The information contained in this entry is based on the notes I took after meeting Dr. Guo and sources I have collected over the years.

Scholar and Warrior

Dr. Guo was born in 1951 in Taiwan and started his martial arts training at ten years old. When he was nineteen, Dr. Guo met his last teacher master Liu Yun Qiao with whom he learnt Bajiquan, Baguazhang, traditional weapons etc. It was through master Liu’s influence Dr. Guo began his research on the military long spear. Since then Dr. Guo has concentrated his attention towards Bajiquan, Baguazhang, Liu He Tanglang and Chen Style Taiiquan. There is an interesting anecdote told to me by Dennis Rovere who have some discussions in the past. When Mr. Guo went to serve his compulsory military service, he was was asked or mentioned about his martial arts training. Mr. Guo was sent to the Taekwondo instructor for a test (an art that was taught following the model of the US army), Mr Guo beat the instructor and was awarded a black belt on the spot.

He moved to the US to pursue graduate studies in engineering and later relocated to Toronto, Canada in 1979 where he founded the Strong Wind Boxing Club (Ji-Feng Quan She, 疾風拳社) to promote the styles he learnt in Taiwan. From that year on Dr. Guo has devoted his time studying Ming military history in regards to traditional weapons manufacturing, their application, and based on his research the creation of training weapons and rules for competition. In 1999 Dr. Guo organized the first Yun Qiao Bei (雲樵盃-Yun Qiao Cup) Da Qiang (大槍) competition in Toronto, Canada. This was followed by a 2001 competition in the same city. In addition to the promotion of the Da Qiang, Dr. Guo also promotes Da Dao (大刀), Shuang Dao (雙刀), Dan Dao (單刀), Jian Shu (劍術) as competitive sports (Bajimen, 2019). During the spear lesson, Dr. Guo showed me a prototype for a double edge sword (Jian) made of wood and a soft foam core, when hit by it one only feels a little slap. Dr. Guo expressed during our conversation the main interest in his martial studies is the practical application of those skills.

Dr. Guo has published articles about mathematical modelling of martial force generation and Da Qiang practice such as:

- “Mathematical Analyses of Silk Reeling Power (Chan Si Jin)”, 1991 won a gold medal award

- “Spear Training: Theory and Its Application”, 2005

- “Traditional Da Qiang – A Study of a Competitive Sport and Its Development”, 2007

- “A Study of Ming Dynasty Military Weapons their Skills and as a Competitive Sport” doctoral thesis at the Shanghai Sports College, received high praise in 2007.

He credits his life in Canada for giving him a different perspective, new ideas and way of thinking to the point of re-evaluating his previous training to what he does today, including the creation of competition Da Qiang. Dr. Guo has visited Taiwan and Hong Kong to promote Da Qiang both as a teacher and even participating in competitions with this weapon in the previous years, he is also promoting the sport in North America.

Battlefield Da Qiang

Dr. Guo makes a clear distinction between civilian/folk spear and the one use by the military. There are ancient references on the use of this weapon, the Book of Tang (Tang Shu) describes the use of the spear as part of the military examinations (Wu Ju) along with archery and physical prowess. (Henning, 2016) The spear has always been considered one the most important weapons used in the battlefield.

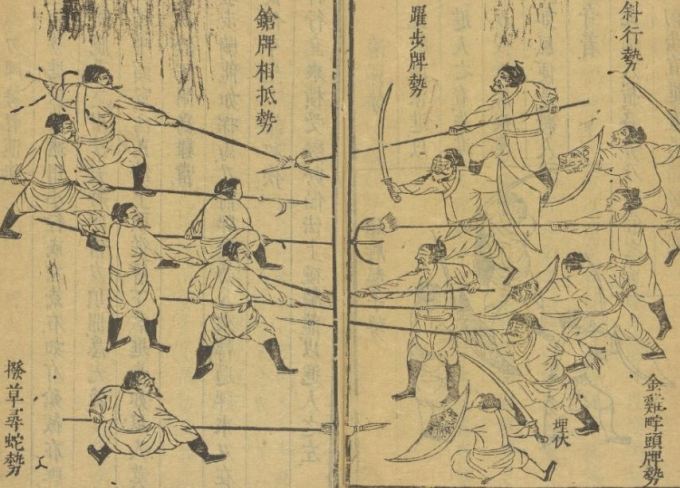

Dr. Guo consulted different sources during his research among them Ming general Qi Jiguang’s Jixiao Xinshu (New Book of Effective Discipline, 1561) and Shoubi Lu (Record of Arms, 1678) by Wu Shu. Of the two treatises Dr. Guo considers Qi’s book as the one providing the most practical and realistic description of spear practice. As a testament of the importance of Qi’s contributions, his work was reproduced in other treatises and encyclopedias both in China, Korea and Japan such as: Illustrations of the Three Talents (San Cai Tuhui, 1609), List of Various Military Skills Interpretation Series (Wu Yi Zhu Pu Fan Yi Xuji, 1610, Korea), Record of Military Armament by Mao Yuanyi (1621), Military Preparations Summary by Cheng Ziyi (1632),The Secret of High Strategy (Heiho Hidensho, 1701 Japan), Tang People Illustrated Teachings Collection (1718, Japan), Comprehensive Illustrated Manual of Martial Arts (Wu Yi Tupu Tong Zhi, 1795, Korea) to name just a few. Dr. Guo points out that none of the sources he studied provide a description on the tactics used to make the techniques work in actual fighting, something Dr. Guo is still working on in collaboration with his students and the main topic for his future book.

In Dr. Guo’s opinion solo practice is considered as folk/flowery martial arts and basic level training, only through practice with a partner one can start to develop true skill in the martial arts, an approach he promotes in his lessons. The Da Qiang has a length between 3 to 5 meters, most of the shafts used by other groups working with the Da Qiang have one basic problem, the spears those groups use are made of wax wood or similar material which is too flexible. Ancient manuals describe wax wood only for weapons like the staff (棍, Gun). In the battlefield the soldiers wielding the Da Qiang were facing an opponent protected by armor, a flexible spear would bend upon impact wasting away the force that otherwise should have been concentrated towards the tip to penetrate the opponent’s protective layer. The stiffness of the ancient Da Qiang was achieved using a multi component construction of bamboo, silk and lacquer in several layers. The back end of the weapon had a metal butt (Zun, 鐏), this detail helps in the correct alignment of the weapon with the arm/wrist. The spears were stiff and light to allow endurance in the battlefield.

Da Qiang Practice

Dr. Guo conducts his classes at the Cultural Centre of Taipei Economic and Cultural Office in Toronto located at 888 Progress Ave, Scarborough. I arrived at 1:30 PM as Dr. Guo and several of his students were already preparing for the lesson. Because I and another person were coming for Da Qiang training, Dr. Guo assigned couple of his senior students to help us out. There were about a dozen students with sparring gear training empty hand skills, a second group was practicing Taijiquan and a smaller group I was with training with the Da Qiang. The entire lesson took 2 hours. Through the lesson Dr. Guo had a very contagious enthusiasm when teaching his art.

In its early beginnings the Da Qiang used by Dr. Guo’s team were made out of solid pieces of wood, in fact Dr. Guo learnt carpentry to manufacture them. Given the safety concerns associated with the spears shattering during practice and causing serious injuries those early spears had an electric conduit cover to enhance the strength and to contain any splinters in the even the shaft broke. The tips were made out of foam and electric tape. One of the issues with the original tip design was that it was hard to know if a proper trust was executed, this led to the development of new tips that now have a “squeaky” device that will only make a noise after a proper trust is executed on the opponent’s body. The early protective gear was only a hockey helmet, now they have besides the helmet a Han inspired fish scale leather armor. The current Da Qiang design is made out of carbon fibers, when practicing with one of them I found these spears to be lighter and stiffer than the wax wood ones I have at home.

The new carbon fiber spears have an additional feature, they are made out of two parts than can be threaded together via a metal screw on one of the halves. This allows for easy transportation and storage. I will now describe from my recollection the main points when practicing with the Da Qiang.

- Stance is close to a horse stance, not too low and not too high.

- As in empty hand practice, the fighting stance positions the torso sidewsys to minimize the target area.

- The back is straight, with a small curvature on the chest.

- Shoulders are down and relaxed (do not shrug).

- Body weight is centered.

- The rear hand holds the end of the Da Qiang with the thumb, index and middle fingers tightly with the end of the spear resting above the hip bone and below the floating ribs.

- The rear arm’s elbow is in line with the spear.

- The lead hand holds the Da Qiang with a loose grip.

- When trusting the rear foot’s toes move forward, do not move the heal back.

- The body rotates engaging the hips during a thrust, much like a punch executed with the rear hand.

- When thrusting the lead hand slides down towards the end on the rear hand and rests on top of it. Lead thumb is over the rear hand’s thumb

- At the end of the trust the weight is on the lead leg without leaning forward, chest is squared towards the opponent.

- The spear’s shaft rests on the abdominal muscles, when blocking the turn of the hands is simultaneously aided by dropping the weigh slightly and using the core. Using the hands/arms only to move the spear will not generate as much power.

- After thrusting quickly pull the weapon back to the initial guard

Endurance/Strength Training

- In order to built strength in the wrist, once the thrust is completed one can hold the weapon for 3 seconds before retrieving it back to the initial stance.

- To test if the practitioner is engaging the hips when thrusting, a partner grabs the end of the spear with one hand. Perform the thrust engaging the hips, if properly done the partner holding the weapon will be pushed back. The arm extension is secondary in this exercise.

- Weight training can be used to develop power and endurance.

Accuracy Training

- Here you partner holds a target e.g. Taekwondo pads or focus mitts on the side, then suddenly he/she lifts the target and the other person thrusts with the spear.

Partner Practice

- Two people armed with spears face each other, they approach with the tip of the spear facing the opponent. Once the critical distance is reached (when you are able to hit the opponent with your thrust, this depends of the practitioner body type e.g. tall vs. short) one-person attacks while the other defends.

- The defense is composed of a slight lean back to increase the distance when the opponent attacks high. As you lean back raise the spear to start the inward blocking motion (this is the easiest to practice and why it is taught first). This is followed by dropping your weight slightly, turning your lead hand inward and drawing a “6” in the air with the tip of the spear. If done correctly the opponent’s weapon with by deflected and your weapon will be pointing to the opponent ready to continue with a thrusting counter attack. The above differentiate the Chinese spear way of fighting when compared with its Japanese counterpart. The Japanese tend to use a knocking/hitting motion to one side type of defense, forcing the defender to have his/her weapon pointing away from the attacker.

- A variation of the above exercise has one person starting with the weapon as if it had been knocked away already and his/her partner is ready to attack, this forces the defender to quickly move to stop the coming attack.

- A second more advance technique consists in a high attack interrupted when the opponent is attempting to block and then quickly retrieving the weapon to attack the middle section.

Rules

The rules try to mimic the battlefield, raising the weapon and then use it to hack the opponent or striking side to side does not award any points. The reason is simple, the spear’s main way of attack is by stabbing, raising the weapon in the battlefield allows the opponent to close the distance negating the spear length advantage. Similarly, striking side to side will cause the soldier to hit his team mates. A proper thrust to the head or body is considered a lethal blow and awards 3 points, the preference is on attacking the torso, given that the opponent can dodge an attack to the head easier. A thrust to the limbs only awards one point as this is not as lethal. In this type of competition there are no weight divisions, it requires skill, quick reactions and mental toughness. Spear fighting is like a chess match, as every combatant attemps to trick his/her opponent in order to land a blow. One challenge pointed out by Dr. Guo is realism, people tend to attack recklessly as they do not feel threaten due to the protective gear and the type of weapon used. The practitioner must always remember the spear is a lethal weapon and treated as such during practice.

Final Thoughts

Now that we have had some time to practice at home, I realize one difficulty when a beginner starts to practice. First off not everyone can wield the weapon correctly due to its weight this causes that the body mechanics are not correct. A weaker person trying to perform the thrust will not have a correct alignment because they are trying to hold the weapon anyway, they can. The main consequence is poor technique. To help prevent this, I started using two shorter staff of different weights to drill the basic movements. As the beginner student builds strength, they can move on to use the actual spear once they have built the correct technique in their muscle memory. Next, I will experiment with the protective gear I obtained in my last trip to China and modify the tips I have which were made out of ¾” hot water insulation filled with silicone and covered with hockey tape. I found these tips to be too hard and one can really feel it when struck. I need to practice more what I learned with Dr. Guo before visit him again in the near future.

References

Bajimen. (2019, 02 17). Retrieved from http://www.bajimen.org/index.php?page=editorial&lang=ch

Henning, S. (2016). Chinese Martial Arts History and Pracice. The Ethnic Publishing House.