In previous posts we have given a quick introduction to the practice of Chinese martial arts in the military during the republican period and the Sino Japanese War. English literature dealing with martial arts practice in the PLA in recent years is at best scarce. The first articles and books that covered this subject were published in 1996 by Mr. Dennis Rovere and Dr. Mizhou Hui. The books by Mr. Hui do not include a lot of details on how the Chinese army trains, any mention of taolu practice and a very general overview about where he learnt his material (Hui, 1996). Mr. Rovere’s publications are based on his experience when training extensively with a bodyguard unit of the military police (Wujing) and the Public Security Administration (Gung An Bu) including translations of Chinese manuals published in the 1990s (Rovere & Huen, 1996). Despite the wealth of information in the above books and articles, a gap exists regarding the development of military combat methods after the liberation. We will try to narrow this gap by consulting training manuals published from the 1950s to the 2000s collected in the past few years. We are currently working on a more detailed coverage of this material in a future book.

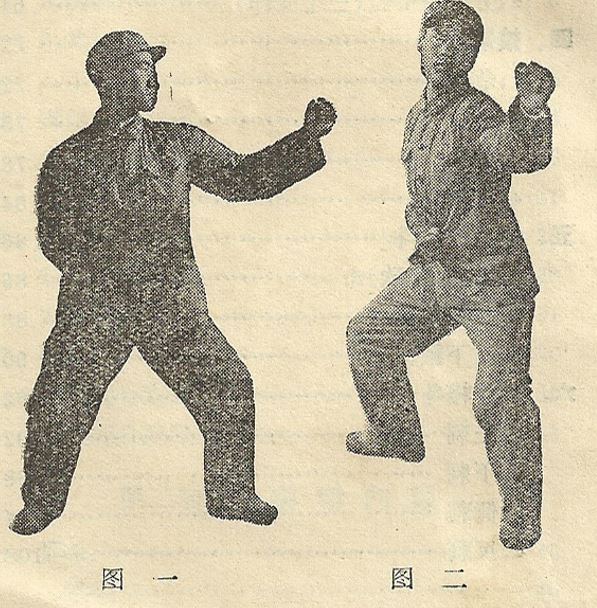

Bu Fu Quan method, 1974. Author’s personal collection

Military Manuals

Martial arts manuals are nothing new, in China scatter references about military martial arts training can be found in different texts, but it is from the Ming dynasty onwards we find entire treatises dedicated to armed and unarmed combat skills. General Qi Jiguang made a distinction between martial arts with a practical combat objective and those practices inspired by martial skills but with the aim of entertainment (Hua Fa/Flowery Wuyi) (Kang, 1995) an important point that differentiates the two approaches even today. During the Republican period the Guoshu proponents looked back to their warrior past as inspiration for the activities organized to promote Chinese martial arts including training manuals some of which we have discussed in previous posts. After the Liberation the CCP moved away from what the Nationalist sponsored Guoshu had done and started the creation of its own Wushu program. Civilians were exposed to a new type of martial inspired curriculum with the main objective of performance and gymnastics, stripping away their original combat applications. The PLA on the other hand translated Russian manuals published during WW2 and used them as template for their early training methods.

Infantry Unit Fighting Textbook (Trial Version), 1965

These manuals were published by government institution such as the Chinese People’s Liberation Army General Staff Military Training Department, the Ministry of Public Security Forces Civil Police Office Group, the Fujian Military District Command Centre etc. The material was published in different formats e.g. books, posters and fold-able brochures; later manuals that appeared from the 1980s onward included those by active or retired military personnel. This material was also distributed as DVDs/VCDs in recent years many of which can be found on the Internet. While competition/ Jing Ji Wu Shu was divided into two very distinctive and independent streams e.g. Sanda/Sanshou (Free Fighting) and Taolu (Routines), military martial arts have preserved the practice of routines as a prerequisite to fighting. While the term Sanda is colloquially used to refer to hand to hand combat, the PLA uses the term Gedou (to Wrestle/fight) in both manuals and training footage we have researched. As discussed in a previous post the earliest PLA’s military training manual we located was published in 1946 commissioned by the Northeast Democratic United Army Jilin (a province bordering Russia and North Korea) Security Headquarters.

After the liberation the 1946 manual which is a direct translation of Russian combat material like the Manual for the Preparation for Hand-to-Hand combat (PNPB-38) published in 1938 was revised and published with two different titles. The first of such books is Sports Teaching Model /Tiyu Jiao Fan in 1952 and Sports Teaching Orders/Tiyu Jiao Ling in 1955. The copy in our possession of Tiyu Jiao Ling covers a wide range of physical education areas considered important for the military including calisthenics, obstacle crossing , grenade tossing, bayonet /entrenching tool/empty hand fighting (nothing resembling sport Sambo), instructions for the design of obstacle ranges, gymnastics, weight lifting, skiing, swimming etc. The Russian influence is obvious as the illustrations are identical to the Russian material. The same manual edited in 1960 has the illustrations changed to depict soldiers wearing Chinese outfits. Another key difference is the inclusion of a short section of Chinese wrestling (Shuai Jiao) in which two individuals demonstrate a few throws and take downs without wrestling jackets. Chinese experiences during the Korean War from 1950 to 1953, the Sino Indian conflict of 1962 and the border clashes with the Russians in 1969 influenced the development of new combat methods for the PLA.

Infantry Reconnaissance Units Specialized Technical Teaching Materials excerpt, 1974. In the 1980s this material was reproduced in a different publication and the illustrations were changed to depict Chinese personnel applying their skills against soldiers from the USA

Chinese Military Combat Methods

Shortly after the liberation Sino-Russo relations were at a all times high, logistic and material support from Russia to the CCP helped with the modernization efforts desperately needed. However, after the dead of Stalin the new head of the USSR Nikita Khrushchev denounced the past leader, which caused an ideological rift in Sino-Russian relations in the early 1950s. This split and the battle field experiences outside China’s borders against larger opponents were some of the reasons the Chinese decided to create a new approach that differ from the Russians. One of such changes was the creation of new sets of routines which are not traditional in the strict sense (coming from one of the many styles practiced during the Republican period) but rather a hybrid of old and new methods.

After the Korean conflict the PLA commissioned the creation of a new combat system that would later be known as Capture Enemy Personnel (for intelligence purposes) Boxing/Bu Fu Quan. This method became and still is taught to military scouts. It includes an empty hand and a dagger routine teaching soldiers the basics of hand to hand combat, capture of enemy sentries for interrogation, conditioning methods to be able to withstand blows as well as to be able to strike with power. Other skills taught to these men consisted of climbing, swimming, driving, shooting, obstacle crossing, Chinese wrestling etc. By 1960 the team developing the Bu Fu method had collected about two hundred different techniques that included wrestling and joint locking techniques. However, they were ordered to simplify the curriculum and by 1964 the final program was then released to the armed forces. Capture Enemy Personnel (for intelligence purposes) Boxing was published/reproduced in different manuals with additional sections thereafter. The version we have from 1974 is a series of fold-able brochures for two empty hand routines and one for dagger including short descriptions for each move without applications.

Capture the Enemy Boxing, 1965

Another method is Capture the Enemy Boxing/Qing Di Quan published as a poster in 1965, the routine in question differs from the one above. It includes a total of 46 movements; to date we have not been able to find background information about this routine. The same name was also used for two completely different sequence which appeared in the form of books in 1998 and 2008. The latter manuals do have an interesting difference from those that appear earlier, mainly in the combat stance adopted, while the former is more “traditional” the main combat stance in the latter books is more modern “kickboxing style” e.g. lead hand is in front of the chin elbows down, rear hand is on the side of the jaw, feet are about shoulder width apart. Capture the Enemy Boxing routine is typically practiced by members of the Wujing (Military Police not to be confused with the PAP – Peoples Armed Police), the term “police” is misleading given that this section covers a wide range of tasks e.g. riot control, anti-terrorism, guarding of government buildings, border security etc.

The bulk of the PLA trains four different routines called Military Boxing/Junti Quan, the first of which was published in 1976 and reprinted several times thereafter. In the 1978 version of Ti Yu Jiao Fan in our possession, the first and second Military Boxing routines are depicted as one continuous sequence. The third and fourth sequences appeared to have been created in the late 1990s and into the 2000s; we don’t have enough information at the moment to determine a more accurate creation date. All of the above routines include the traditional elements of Chinese martial arts such as kicking, punching, throwing and joint locking techniques.

School pupils demonstrating a knife routine

Armed Combat

While the above routines are for empty hand fighting against armed/unarmed opponents the Chinese military has also developed routines using the bayonet, dagger, batons with different lengths, baton-shield and belt that we are aware. Curriculum for improvised weapons and ground fighting are also given to Gung An female recruits (Rovere & Chow, 1996). During the Republican period Pi Ci/Chop and Stab skills were practiced with the Dao and bayonet, the PLA on the other hand has Ci Sha/Stab and Kill techniques using the bayonet. The latter is a combination of different methods that were taught during WW2 including Russian material. There is a short bayonet routine we have found reproduced in a 1980s manual by a member of the military; however no background information is given.

This sequence includes attacks with the bayonet, the butt of the weapon and blocking techniques. In 1972 the Infantry General Staff Headquarters published a draft manual titled Infantry Detachment, Stab and Kill, Explosives and Geotechnical Teaching Material. The combat skills using the bayonet have the soldiers wearing a modified version of Japanese Jukenjutsu protective gear practicing fighting methods against a partner on different terrain and combat scenarios. Military dagger (two edges) is part of the Bu Fu Quan sequence; however it is not the only one.

The Wujing has at least two different routines, where the practitioner performs half of the sequence using a reverse grip and the second half with forward grip. In addition to attacks with the blade kicks, sweeps, blocks with the arms are also included (Rovere D. , 1998). Anti riot baton, baton and shield are also practice by the Wujing and units with crowd control tasks. In 2002 the Wujing developed a long baton (1.5m) sequence called Anti-riot/Emergency Staff also being taught to civilians of the Han ethnic group in the Xingjian region after the bloody clashes that took place in 2009.

Chinese soldiers drilling with the bayonet, 1970s. Author’s personal collection

Arrest and Control

Methods to be used for arrest were also developed earlier than 1964 when the manual To Capture Skills Teaching Material/ Qin Gu Jishu Jiaocai was published by the People’s Republic of China Gong An Troops Headquarter. This manual was issued for experimentation using the methods developed and tested at the Gong An college, it replaced material previously taught and known as Application of Skills. In a 1986 manual titled Capture the Enemy Technical Actions by the Chinese People’s Armed Police Force Headquarters an empty hand routine along with applications for arrest and control are illustrated.

All of the above methods are practical in nature, propaganda footage we have found show both military and police units learning routines/forms, followed by the usage contained in the sequences first in a controlled manner progressing to free fighting against armed/unarmed opponents. Conditioning exercises are also included blending traditional and modern training methods. Even though, in the early years these programs were reserved to members of the PLA and CCP’s approved “militia”, in later years the material is also taught to school and college pupils during their military camps organized on a yearly basis. In late 2017 the South China Morning Post and other media outlets reported how a BJJ black belt was working to introduce this art to the Mainland and Hong Kong police.

The study of modern and traditional methods by security forces in China has/is a normal occurrence; the article seems to hint that police forces do not have a standard curriculum which is not true. In our opinion the article is an effort to sell BJJ as a more appropriate way to handle suspects using a sport method that does not fully cover the realities of street altercations where multiple opponents, difficult terrain and weapons are used against police personnel. Despite the poor human rights record of the Chinese government, we have found several examples where an armed suspect (bladed weapons are common given strict gun control regulations) has been apprehended using empty hand techniques and tools developed for that purpose (a similar situation has led to officers discharging their firearms and killing the suspect in North America) this does not mean the Chinese police shy away from shooting suspects when considered “appropriate”.

Chinese soldiers sparring with bayonets, 1970s

Conclusions

We have presented a high level overview of the development of combat methods taught to units of the PLA which include empty hand and armed skills. The material in the early years made use of Russian sources, but after the rift in political ideologies and the experiences in conflicts against other nations the Chinese military started to develop their own training methodologies. Routine training is used in the early stages and it is followed by the applications of the movements; despite the fact that military martial arts are a blend of old and new they do follow the traditional Chinese way of training such skills unlike the development of civilian martial arts after the Liberation. Nowadays military methods are also taught to school pupils and civilians as part of the military camps and in areas where the Han population has come into conflict with minority groups.

Bibliography

Hui, M. (1996). San Shou Kung Fu of the Chinese Army. Boulder: Paladin Press.

Kang, G. (1995). The Spring and Autum of Chinese Martial Arts. Santa Cruz: Plum Publishing.

Rovere, D. (Director). (1998). Chinese Military Bodyguard Knife Combat [Motion Picture].

Rovere & Chow, (1996). Chinese Military Police: Knife, Baton & Weapon Techniques. Calgary: Rovere Consultants International Inc.

1 Comment