By William A.

Note: Updated on 8/12/2017

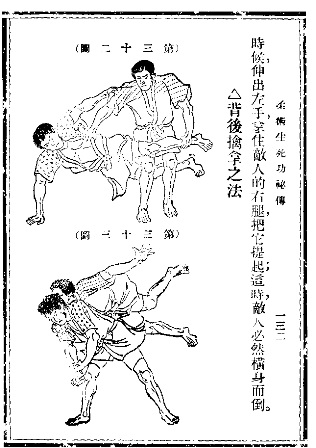

When Japan was forced to open its borders to foreigners beginning the Meiji Restoration, it also helped spread Japanese culture overseas in the form of movements like Japonism (from the French Japonisme) or the interest for Japanese objects from around 1872 onwards. This movement influenced European arts and culture, even though some Japanese elements had already entered the west through the Dutch trade missions during the Tokugawa period (1609 to 1868). The open doors era also translated in the appearance of martial arts books as oppose to secret scrolls only available to a selected few. The earliest Jiu Jitsu book for the general public we located was published in Japan titled “Secrets of Japanese Jiu Jitsu, Sword, Staff and Rope Restrain” in 1877. Several other books followed which help in the propagation of such skills outside dojos. The influx of foreigners to Japan gave them the opportunity to access this material, but also to meet and learn these skills directly from the source.

The earliest publication mentioned in Russian sources introducing Japanese martial arts appeared in 1895 through a St. Petersburg newspaper article titled “Essays of unknown Japan” (Russian Jiu Jitsu, 2017). In it the author introduced its readers to the virtues of the “Japanese struggle – Jiu Jitsu” (Дзю-дзюцу/ Жиу-житсу). The period from 1905 to 1909 saw the creation of various sports associations, usually on a voluntary basis to teach Jiu Jitsu; pre-revolutionary Russia began its relationship with the Japanese art from publications of the time in other European countries. This is due to the fact that during this period there was a lack of competent local Jiu Jitsu teachers. These people were for the most part “self-taught” by books that had been translated to the Russian language. As an example of English language Jiu Jitsu books are those by Irving Hancock published as early as 1903, those authored by Frenchman Emile Andre and others were also translated (Russian Jiu Jitsu, 2017).

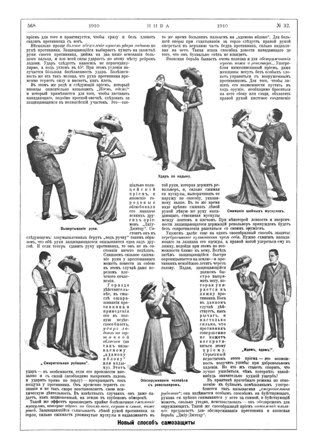

One of the first Russian Jiu Jitsu books was published in 1905 titled “Japanese Physical Education” by Ivan Dmitriyevich Sytinym followed by Andrey Anokhin’s “Psycho physiological Gymnastics” in 1907. The latter included a section on Japanese Jiu Jitsu exercises translated from German sources. Similar books would be published in the following years, some of which were used for police training. As Jiu Jitsu acceptance grew, government institutions also published how to manuals; the Ministry of the Interior issued “33 Attacks, Defences and Disarms from the Japanese System of Jiu Jitsu” edited by Captain Dèmerta. By the year 1910 a new athletic arena open its doors to teach Jiu Jitsu in Moscow by a teacher of the local police (Russian Jiu Jitsu, 2017). Other authors continued publishing articles and books to encourage training in the art by men and women alike, stating the health benefits of such practices. Imperial Russia media outlets also published articles on Jiu Jitsu like the NIVA magazine in their issue No. 30 in 1910 titled “A new way of self-defense” including some illustrations; in 1911 the same magazine published the article “Self defense for women” all of the above mirrors the interest in other European countries towards Japanese methods of self defense.

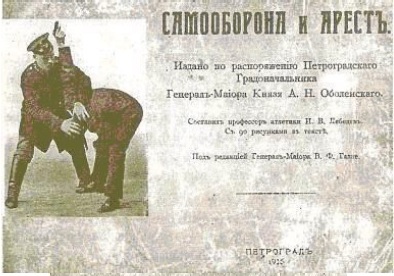

The implementation of Japanese martial arts for security services continued and by 1915 I.V. Lebedev published “Self-defence and Arrest “in Petrograd. This book became a police manual by orders of Petrograd’s Mayor Maj.-Gen Prince Sergei Alexandrovich Obolensky. The fast development of Jiu Jitsu came to a halt when the 1917 October revolution that toppled Czarist Russia happened. Prior to the revolution other combat sports were also practiced e.g. English boxing, wrestling, fencing and French boxing. One of those coaches that travel to Russia and left a deep mark in the development of Russian sports community was French born Ernesto Loustalot (1859 – 1931) who was invited to teach sports at the Imperial School of Jurisprudence in St. Petersburg in 1897. Loustalot was one the first athletes who introduced both French and English boxing as well as initiator of the first public boxing match in 1898. Loustalot was also the boxing and fencing coach for the Nabokov, an aristocratic family whose son Vladimir Nabokov became a renown writer. After the Revolution, he remained in Russia and from 1919 on worked as a teacher of physical training and sports in the Higher School for Naval Officers in the famous Admiralty building (Sklepikov, 2017).

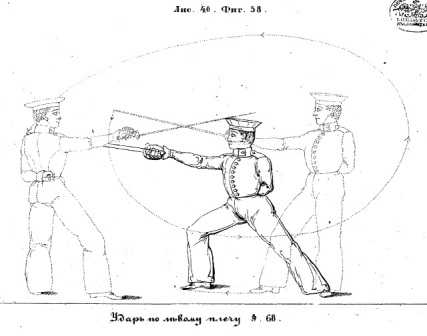

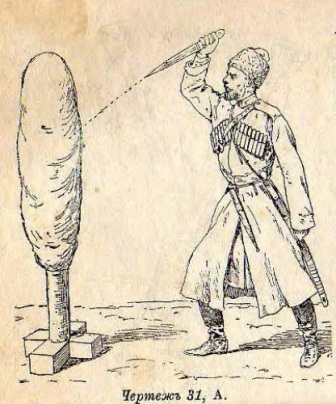

Other combat manuals were available in Russia prior to the introduction of the Japanese systems. The Russians published a translation of a French fencing manual with sword and saber in 1817 titled “Traité sur La Contre-Pointe” (Treaty on the Counter-Point) by Charles Kray. A different manual published in 1837 included additional battle skills using the bayonet “Rules for training infantry to fight for use by skirmishers in single combat during the war” published in Saint Petersburg which seems to depict skills also from the French army. In 1843 “Rules of the Art of Fencing” included skills with the sword, sabre, bayonet and quarter staff. Finally the “Drill for Cossack Service” published in 1899 included training material with the spear, saber and dagger. Despite the study and practice of combat methods the events that took place during the Russo Japanese war (1904 – 1905) might have contributed to an evaluation of their approach to military training.

” At some of the forts men fought at close quarters, bayonet to bayonet, and it was once again shown that, though the Russians have the advantage of size and weight, they are no match for the quicker and more skilful Japanese” (Cowen, 1904)

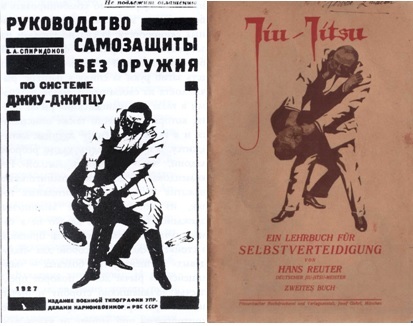

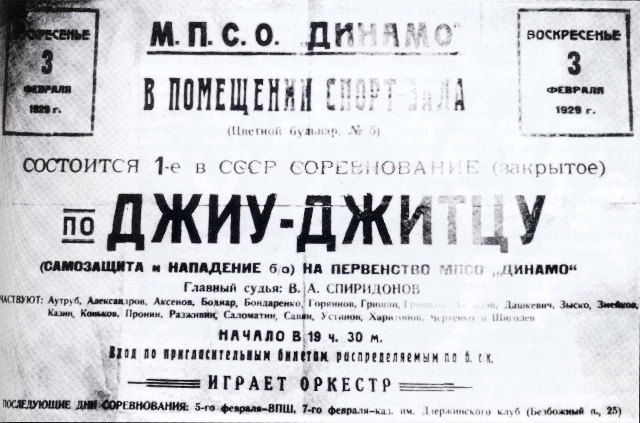

The Dynamo Sports Society created in 1923 in the Soviet Union together with Armed Forces Sports Societies and Voluntary Sports Societies, made up the universal system of physical education and sports of the USSR including the practice of combat sports (Edelman, 1993). In 1927 Viktor Spiridonov published the book “Guide to self-protection without weapons system of Jiu Jitsu”, in its introduction there is a line that states the book was approved for physical training of the Red Army and the Central Board of the Proletarian Dynamo sports societies. Spiridonov book’s cover was copied from a two volume German book published in 1924 by Hans Reuter. Other authors published similar books among them Afanasy Ivanovich Butsenko. Butsenko published “Self-defense without Weapons (Jiu-Jitsu) and its Application for Operating-Peasant Militia of the USSR” in 1928. The author of the book was a veteran of World War I and later became a member of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine. Russian sources point out Butsenko’s book was a copy of a 1926 German book by Erich Rhan (Russian Jiu Jitsu, 2017).

Another important figure is Neil Oznobishin Nikolaevich who was born from a noble family, but became a circus performer. With the circus, he traveled to different countries, this gave him the opportunity to learn many languages and sports like boxing. In 1915 he took part in the first boxing championship in Moscow and between 1918-1926 as some sources state he also trained soldiers of the Red Army. In 1930, the publishing house of the NKVD (The People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs) published Oznobishin’s book “The Art of Unarmed Combat”. As a result of false accusations in 1941, he was arrested and exiled for 5 years in Kazakhstan. His fate after that is unknown. In his book Neil Oznobishin criticizes what he calls “degeneration” of arts meant for combat into mere sport, a familiar argument that still finds echo today.

“…The result of all this was that in Europe the art of self-defense, for practical purposes (i.e. the preparations for serious combat), degenerated into gymnastics of self-defence and sport and as such, continues to be taught to the masses. Look at French boxing, from serious practice it already has deteriorated into a gymnastic exercise. English boxing has evolved into a means of physical development, and the sole purpose of most modern boxers is competition. Jiu Jitsu, thanks to those who are barely acquainted with it, it is presented to us by ignorant teachers as a partner acrobatic show. Finally, knife fighting, the most common kind of melee combat of the Middle Ages, in modern times is studied only by hooligans” (Oznobishin, 1930)

While all of the previous work had focus on Jiu Jitsu, there is one pioneer who contributed with his knowledge of Judo and other Japanese systems to the development of what would later be known as Sambo. Vasily Sergeevich Oshchepkov was born in Sakhalin in 1893 from a state convict and peasant widow and became an orphan when he was 11 years old. After Sakhalin became Japanese territory the archbishop of the Russian Orthodox Christian Church opened seminars in Tokyo, it’s here where Oschepkov received training to become an interpreter for the Tsarist army after his success as a student. In 1908 a Judo study group was opened at the seminary and three years later he would be admitted to Jigoro Kano’s Kodokan in 1911 and received his first Dan in 1913 (Gorbylev, 2010). Upon returning to Russia in 1914 Oschepkov started to work as an interpreter to the counterespionage body of the Frontier Guards and later on he was transferred to Vladivostok which gave him the opportunity to travel in several occasions to Japan to continue furthering his training and by 1917 received his second Dan making him one of the few foreigners at the time and the only Russian national to achieve such honor.

While in Japan Oschepkov was exposed to other Japanese fighting arts like Sumo and Jukendo (practices that were common in Japan at the time) given that he was the only individual who had received training directly from the source and unlike the many instructors back home that had learnt through books and experimentation, his contacts allowed him to organize matches between his team and Japanese exponents. After the fall of Tsarist government Oschepkov served as intelligence officer from 1925 to 1926 in Japan which did not allow him to concentrate full time in his combat research interests, nevertheless he took any opportunity to study books and the occasional escapee to the Kodokan and Judo clubs (Gorbylev, 2010). After returning to Vladivostok he continued his research along with other combat sport specialists who allowed Oschepkov to compare the merits/flaws of English boxing and Savate. His attention also included studying potential contributions from ethnic wrestling styles as well as Greco-Roman wrestling that would later be incorporated in to a new combat system and sport (Gorbylev, 2010). In 1927 he published an article in local military news paper outlining the importance of hand to hand combat as well as describing the developments in the area at the Japan’s Military Academy; Oschepkov continued writing and demonstrating his art until his efforts caught the attention of the Red Army leading to a demonstration before army physical training instructors from the Soviet Union in Moscow in August 1928 (Gorbylev, 2010). Oschepkov continued promoting Judo at the State Central Institute of Physical Culture (GCOLIFK) in 1931 and from that year to 1937 he was able to work with the “Department of Defensive and Offensive Methods,” alongside other combat sport specialists, he even reached out to V. Spiridonov to work cooperatively without success.

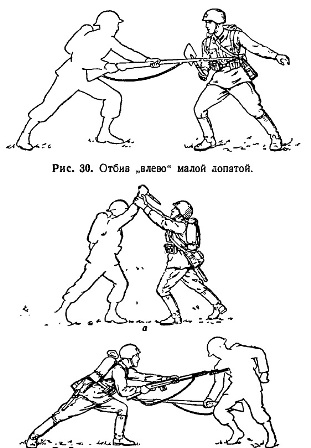

As described earlier Spiridonov’ system was based on European Jiu Jitsu learnt through books and experimentation to which elements of Greco-Roman and Catch wrestling have been included, this system had been adopted within Dynamo in the 1920’s and had a strong influence allowing Spiridonov to be able to depose Oshchepkov from all Dynamo subdivisions and the Central Higher School of Militia (Gorbylev, 2010). After the Japanese invasion of China in 1937 the Russo-Japanese relationship soured leading to the stop of Judo development and the incarceration of Oschepkov on the suspicion of being a Japanese spy, nine days later he died in prison (Gorbylev, 2010) a sad end to an outstanding individual. Oschepkov’ students continue with the work and in 1938 a statement was issued declaring that “Free Style Wrestling” was based on native practices (erasing in one stroke any mentioned of Judo or any Japanese influence) the same year Order Number 633 made official the development work taken place in the decades before. In 1940, V. Volkov, a student of both Spiridonov and Oshchepkov, published a manual for NKVD schools titled The Course of Self-Defense without Weapons—Sambo using for the first time the Sambo abbreviation and including techniques from both teachers (Gorbylev, 2010).

Additional sources used by the Soviets in their pursue to develop an all encompassing hand to hand combat system came from the USA; in 1927 G. Kalachev published a Russian translation of a US Army bayonet manual published earlier titled “Bayonet Fighting (from foreign sources)” published by the Central Printing Office of the People’s Commissariat of Education. The original manual would be republished in 1940 in the USA as the “FM 23-25 Basic Field Manual Bayonet, M1905”. At this point in our discussion it is clear that Japanese martial arts and western systems had played a very important role in the development of Russian combat arts as well as the enormous Russian efforts to create a system that was all encompassing, how much of this material was if any transmitted to the Chinese when the Whampoa Military Academy opened its doors in 1924 is the subject of the following section.

“Hitler robbers want to take our land, our bread and our oil. They want to restore our country to the power of the king and landlords, Germanized free peoples of the Soviet Union and turn them and slaves of German princes and barons. This will not happen ever! Death to the fascist vermin! The enemy can not stand the Red Army bayonet attacks. Bay fascist bastards bullet, grenade, bayonet!

SOLDIER! Deadly and insidious enemy of your country – German fascism – armed to the teeth with firepower and the machinery of war. However fascist hordes avoid meeting with us in the melee, for our fighters showed that it was not and they have no equal in courage and dexterity melee. But with the technique and tactics of the enemy we should seriously be considered. It is necessary to master the art of the approach of the enemy, the arts closer to him on the battlefield. Must be able to move in the battle so that the enemy’s fire, which would force it was, could not hold our maneuver, and our offensive attack. So fierce battles with our enemy: – to move faster and covertly – throw a grenade far and accurately, – beat with a bayonet and butt tight!” (Tarasov & Karpa, 2012, 1941)

The Whampoa Military Academy Curriculum

After the Russian Revolution, attention was turned towards countries who could also continue the struggle against capitalism and its agents. Sun Yat Sen, father of the Chinese Republic found support for his cause in the Soviets who were more than willing to provide financial and material aid to create a nationalist army to unify the country, once Sun was able to return to China after the fall of the Qing Dynasty. Hundreds of Russian men and women took upon themselves to continue the spread of the revolution in a foreign land and volunteered to form the contingent of advisors that travel to China. One of such men was Alexander Cherepanov who took part in the storming of the Winter Palace. In 1918 participated in the Civil War on the Western Front, became the regiment commander, chief of staff and then a commander of brigade. In 1923 he graduated from the Military Academy of the Red Army and by 1924 became the chief military adviser to the Whampoa Military Academy. In his memoir Cherepanov wrote:

“At a meeting with Sun Yat-sen it was decided that the main profile of the school will be for the infantry with a training period of six months. In addition, there were special classes: Artillery (60 cadets training period 9-12 months), an engineering (130 students, 9 months), communication (30 students, 9 months), supplies (60 cadets, 6 months). Machine Gun class of 120 people was composed of infantry cadets and was designed to be only a 20-hour course…

Later, training political workers was organized in the school, after which she became officially known as the Central Military and Political School…

The school has also established Russian language classes (25 people), fencing and gymnastics…

The teaching staff was recruited from officers with sufficient general culture, but with a very different military training: some finished military schools abroad, mainly in Japan, the others – the old Chinese military school in Baoding or provincial military school at the private army of a warlord…” (Cherepanov, 1964)

Chinese sources list in general terms what cadets were taught such as: Tactics and strategy, intelligence, geography, war history, troop mobilization, weaponry, fortifications, political thought, Sun Yat Sen’s Three principles of the people, foreign languages e.g. Japanese, English, French, Russian and German. On April 6, 1927, Chinese authorities conducted a raid on part of the Soviet Embassy compound in Peking, where several documents were seized dealing with Soviet activities and intelligence gathering on Chinese soil. The documents point out at the use of outdated doctrines as:

” The reason for it is the absence of proper instruction, the inertness of the old officer-personnel, and especially the ignorance and inexperience of the junior officers, who are graduates of the schools of the National Revolutionary Army. Besides, the drill regulations and the [2] textbooks on tactics which the army uses are extracts compiled from the German and Japanese regulations which were used in those armies in the beginning of this century and which do not agree with the methods of modern warfare.” (Willbur & How, 1989)

Physical training was also questioned in the following terms:

“Athletics. Athletics are completely neglected in the Chinese army, although they are very clumsy (e.g., they do not know at all how to jump). Time allotted to athletics is seldom to be found in the training schedules and there is only one instructor to a company. It is therefore natural that the movements are made drowsily and incorrectly, and as they are never corrected, they do not develop the muscles and the energy but rather weaken the latter. There is no athletic equipment and no facilities for field sports. It is necessary to have the athletics before lunch and to divide them into calisthenics, gymnastics on apparatus, and field sports. The simplest equipment ought to be procured and facilities for field sports arranged for this purpose.”

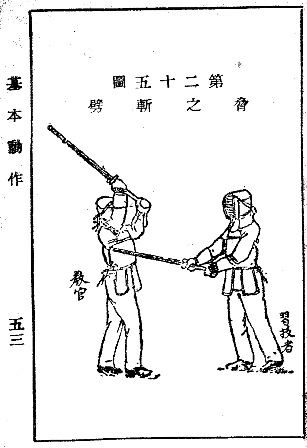

Given that the Russians considered their hand to hand combat research secret, the fact that Russian Free Style Wrestling as a system was not officially recognized before 1938, the use of the acronym Sambo referring to a Russian combat system after 1940 as developed from the the above evidence using Russian and Chinese sources in which no mention of such classes were ever part of the curriculum for Chinese cadets at Whampoa, we can refute the assertion of Sambo practice in the Military Academy. Moreover, even Chiang Kai Shek who visited the Soviet Union in 1924, was not impressed with what he saw at the time. The Chinese were very familiar with Japanese martial arts through those students who graduated from Japanese military schools, the fact that the Chinese had translated Japanese Jiu Jitsu, Judo and Sword-Bayonet manuals and the Central National Arts Academy research trip to observe martial arts training methodologies during the 9th Far East Games in Tokyo in May 1930 (Gewu, 1995) demonstrate the Chinese interest to “know your enemies and know yourself”.

As the Sino-Japanese war raged on, the Nationalist and Communist forces fighting the Japanese made use of native skills in battle. The officers trained at the Military Academy in Nanjing learnt Xingyi Quan for both empty hand and weapons fighting (Rovere, 2008) as well as had German drill instructors after the Russians were expelled, footage of Chinese officers training also show them practicing western styles calisthenics and athletics. The military academy was relocated to Chengdu in the province of Sichuan after the Japanese onslaught, training footage shows cadets performing routines promoted by the Central National Arts Academy (Zhongyang Guoshu Guan). When the Japanese launched their anti guerrilla campaigns in Manchuria against the Communist Northeast Anti-Japanese United Army starting in 1931 it drove the communist into Russia to escape annihilation in late 1942. It is after 1942 when Chinese communist forces received training from the Russian Field Manual of the Red Army published in 1941 and reprinted with modifications thereafter. An important detail about the Russian manual is that it included a small number of armed and unarmed combat skills none of which resemble sport Sambo for obvious reasons. The Red Army’s material was also used as template for the 1942 “The partisan’s Companion, The Guerrilla Fighter’s Handbook”. The Nationalist troops stationed in Burma in 1942 received training that included hand to hand combat from the US army’s FM 23-25 Basic Field Manual, with some of these skills still prevalent in the Taiwanese armed forces.

Conclusions

The development of Russian martial arts owns a great deal to Japanese and western systems. The need to create a versatile combat program lead to the study of different sources at a time of war in armies worldwide. Russian and western influence in Chinese hand to hand combat training took place as the Sino-Japanese war was reaching its climax and not as early as some authors have suggested. The study and comparison between Chinese and Japanese systems was a necessity in order to understand the capabilities of the enemy and how to improve upon to beat them.

Bibliography

Cherepanov, A. (1964). Notes from a Military Advisor in China: From the history of the First Revolutionary Civil War (1924 – 1927).

Cowen, T. (1904). The Russo Japanese War. Londonc: Edward Arnold.

Edelman, R. (1993). Serious Fun A History of Spectator Sports in the USSR. Oxford University Press.

Gewu, K. (1995). The Spring and Autum of Chinese Martial Arts. Plum Publishing.

Gorbylev, A. (2010). Sambo. In T. Green, Martial Arts of the World an Ecyclopedia. ABC Clio.

Oznobishin, N. N. (1930). The Art of Armed Combat. NVKD.

Rovere, D. (2008). The xingyi quan of the Chinese army : Huang Bo Nien’s Xingyi fist and weapon instruction. Blue Snake Books.

Russian Jiu Jitsu, F. (2017, March 23). History of Jiu Jitsu in Pre and Post Revolutionary Period.

Sklepikov, A. (2017, March 22). Loustalot: The Nabokov Family Trainer. Retrieved from https://www.libraries.psu.edu/nabokov/lousta.htm

Tarasov, A. A., & Karpa, B. (2012, 1941). Destroy the enemies in Hand-To-Hand Combat.

Vasili Oshchepkov. (2017, March 22). Retrieved from Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vasili_Oshchepkov

Willbur, C. M., & How, J. L.-y. (1989). Missionaries of Revolution Soviet Advisers and Nationalist China 1920-1927. Studies of the East Asian Institute Columbia University.

Actually AA Harlampiev created Sambo system that was officially recognized.

Thanks for stopping by Boris correct me if I am wrong but Harlampiev version was recognized in 1938. Also his was mostly a sport yet it is not what you see in the Red Army’s combat manuals. I left out a bit more details for brevity, however even AAH used Judo as a base for his system. The first oficial Sambo school in China opened couple years ago:http://www.sportspromedia.com/announcements/first_sambo_school_is_opened_in_china

Very nice and comprehensive post – thank you for that!

Cheers

Jason

Thanks for your comment Jason, glad you liked it.

Thanks for stopping by Alexey. Please write a detail description to correct them, also these entries are by no means an exhaustive study of these topics as it would be case for a peer review journal. If you have a better narrative about the subject by all means share it and I’ll link it here.

I would recommend you to refer to the Sambo section in:

Martial Arts of the World [2 volumes]: An Encyclopedia of History and Innovation

by Thomas A. Green (Editor), Joseph R. Svinth (Editor).

As to the physical training in 中华民国陆军军官学校, the information on the subject is available even in Soviet sports publications of 1920s. And I am sure, the current Chinese sources contain much more detailed information.

Thank you for your replay. I have the books you refer to but the 2001 ed, which had a very short entry on Sambo. I did find that the 2010 edition has your article, which indeed is very detailed and I had already asked for it to clean up my entry. As for the Chinese section I prefer not to expand on it as I want to leave it for future posts. Thanks again for your insights.

The topic is of great interest. So, I personnally would be very grateful if you will find it possible to expand it. And I am really sorry, but I could not find the name of the author of the entry… Wish you good like!

Sorry for misspelling. Of course, I wish you good luck! 🙂