By William A.

Note: This illustration appears to depict someone who looks more like Gichin Funakoshi father of Shotokan Karate rather than Chouki; Japanese sources point out this editorial mistake was a point of bitter rivalry between the two men.

Western influence in Japan and China was a source of national self-reflection triggering at times violent social, political and technological changes. What defines a nation’s identity found echo among both intellectuals as well as the common man who looked back to their rich at times romanticized history for those elements that could define the soul of their nation. This process did not take place without resistance from those who wanted to ensure their countries follow the path of the west and their superior technology. The Chinese Self Strengthening Movement (1861 to 1895) and the May 4th (1919) Movement looked at the west for inspiration, in general terms while the former had its focus on military technology to overcome defeats at the hands of foreign powers. The latter look into western political institutions and thought rejecting traditional Confucian ideals as one of the causes for China’s weakness leading to the fall of the figure of the Emperor, the abolition of the Imperial Examinations, the rise of the Nationalist and Communist parties etc.

When Commodore Perry’s black ships arrived at Tokyo’s harbour in 1854 demanding a trade agreement with the USA, it lead to the influx of foreign capital, opening of more ports with western residents, trade agreements with other nations, the spread of Christianity etc. All of the above triggered the downfall of the Tokugawa Shogunate and their closed-door policy, which in caused the creation of a central government with the Emperor as symbolic head.

Western influence in Asia started to trickle down way before the more dramatic changes that took place from the 19th century onwards. Firearms technology had been introduced to Japan as early as the 13th century from China, with the matchlock coming from Portuguese sources sometime in 1543. The Japanese were able to mass produce these weapons and used them in subsequent internal and external military campaigns. Muskets were also introduced from Japan to Korea in 1590 as a gift to Korean envoys on a fact-finding mission to determine whether the Japanese were planning an invasion of the peninsula. King Sonjo and his officials made the faithful decision to merely kept these weapons in the imperial armory rather than learn to manufacture them. Minister Kim Ugnam went as far as to say to the king that bows were superior to muskets in power, a comment the king tried to correct. During the Imjin War (1592 – 1598) the Japanese used muskets with great effect against the Koreans. (Byonghyon, 2002).

The Northern Silk Road was one of the main sources foreign goods came into China, it is through this route the Polo brothers and Marco Polo arrived and struck a friendly relationship with Kublai Kahn for 17 years. The Jesuit missions to China between the 16th and 17th centuries introduced western sciences, mathematics, arts , astronomy and Christianity while at the same time exposing the west to Chinese thought, history and culture. Western style cannons might have been introduced either by pirates or the Portuguese as early as 1521 and later with the assistance of German Jesuits a foundry in Beijing was opened to produced such weapons.

Despite the fact that exchanges between the west and Asia were nothing new, the changes that took place during the XIX century onwards due the western pursuit of new markets deeply changed the social landscape of cultures that for a long time have been shelter for the most part from anything foreign. We will now turn our attention to some examples illustrating how the native fighting arts became a link to a proud past.

The Japanese Case

The changes that gave way to the Meiji Restoration (1868 – 1912) which included military reform did not come peacefully, as a result the Satsuma Rebellion of 1877 is an example. The members of the revolt were dissatisfied men who once were part of the samurai class; the rebellion would eventually be quailed by the modern Japanese Imperial Army. The main western military influence during the Meiji period came from the French up until the defeat of France during the Franco Prussian War of 1870 – 1871. After the conflict the Japanese turn their attention towards German military tactics and thought. Despite the latter shift, French influence was still present to the point that classes by German officers had to be given in the French language (Lory, 1943). The need to modernize the nation by the introduction of western models included athletic centres for track and field, baseball, volleyball and gymnasiums by the Public Welfare Ministry instigated by the Army aimed to physically prepare its future recruits.

The Japanese also turn their attention to their warrior past and use it to inspire old and young on the glorious martial heritage in the form of the samurai warrior image and his unflinching loyalty towards the Emperor. The samurai’s loyalty to his lord was tranmitted to the soldier and sailor as their essential duty and without that the new man of arms was merely a puppet (Lory, 1943). These ideals were based on a romanticized notion of the warriors of old, yet it was a common theme promulgated to the population in general and a daily reminder to the members of Japan’s armed forces. The propaganda machine used tales from the past such as the Forty Seven Ronin told many times over in the barracks, school rooms and homes throughout the nation, a reminder to all of what the utmost duty of a true warrior was.

Japanese soldiers disliked the emphasis in sports practiced by western armies e.g. football/soccer, rugby and some units preferred wrestling (sumo), but in general bayonet training was a favorite; Kenjutsu (fencing) practice was regarded as the privilege of officers. Fencing and bayonet training was considered important to instill a taste for aggressive attack and the Japanese Katana replaced early western style officer swords given the Katana’s connotation as a sacred symbol. Officers and soldiers also engaged in other native martial practices such as archery, Jiu Jitsu and Judo (Lory, 1943). Similarly the civilian population also practised native martial arts and thanks to Japan’s militarist, martial arts popularity increased both inside and outside the country.

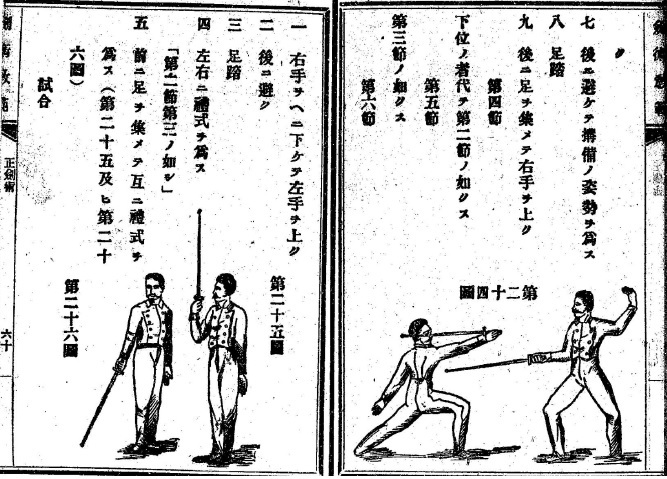

Early illustrated military manuals show western influence on physical training, as an example a gymnastic manual was published in Tokyo titled Model to Teach Gymnastics – 1888 with sections of this manual reproduced in 1892 and 1902. Similarly in 1889 a three-volume manual covered western skills with the bayonet and sword titled Sword Techniques Teaching Material. In 1902 the Japanese published the Military Affairs Manual a standard for the Japanese armed forces to teach the skills of bayonet, katana and tanken (short sword) which also included sections from the Model to Teach Gymnastics manual.

The Military Affairs Manual shows for the first time the use of Japanese design protective gear during pair practice and sparring; subsequent manuals for close quarter combat with weapons were published in 1907, 1908 and 1909 onwards with small modifications. What is interesting to note in the later publications is that fencing using one hand as in the 1892 version was not as prevalent when compared with the two hand grip techniques, chopping attacks were preferred to thrusting for sword fighting; as for bayonet techniques the deep lunge, double hand thrust where both hands hold the stock of the rifle and the single hand thrust were discarded.

The Chinese Case

The Chinese also looked to modernized their institutions to avoid further defeats at the hands of foreign nations yet not as successful as the Japanese. While the New Cultural Movement wanted China to adopt western models the School of Nation Essence sought the preservation of native practices. In the end a mixture of the two ideologies took place. Chinese student were sent to Japan, USA, Europe and Russia to learn from those countries as well as advisors, teachers and other came to China with new ideas. Military academies open their doors as early as the Qing dynasty with the Tianjin Military Academy with German advisors in 1885, it was followed by the Yunnan Military Academy founded in 1909, then the Baoding Military Academy founded in 1912 which followed Japanese and German training models and finally the famous Whampoa Military Academy in 1924 with Russian advisors until they were expelled in 1927.

As a result of the many foreign influences that were competing for attention, it encouraged a wave of Chinese nationalism to practices like martial arts. Ma Liang`s New Martial Arts of China, the National Essence Athletic Association were the first ones that appeared. The increasing Japanese aggression towards China and the fanatic emphasis on Bushido was countered by the formation of martial arts organizations like the Tianjin Warriors Society in 1912 as a means to encourage China`s warrior spirit followed by other organizations with similar goals (Yan & Li, 2011). The creation of the government sponsored Central National Arts Academy also helped promote martial arts throughout the nation, even though western physical practices were still popular. From all these multiple sources it was the Japanese models that were used/compared against by the Chinese forces. There is footage and written evidence that the Chinese replicated their foe`s protective gear designs used in bayonet and sword training. As a side note, we are working on a book based on Chinese manuals published by both the nationalist and communist that have never been translated; we hope to complete this project at the end of the year.

The Whampoa Military Academy translated and published a Japanese Sword and Bayonet manual in 1928, other similar publications were also translated by other institutions; the assertion of Russian advisors teaching Sambo to the Chinese does not hold to scrutiny when looking at the evidence (a topic for a future article). Suffice to say that both memoirs of such advisors and Russian records confiscated by the Chinese at that time do not support that theory. We have to be careful not to jump to the conclusion the Chinese merely copied combat skills given that the government’s goal was to instill national pride and will to resist in the population at large; it would have been very difficult to do so if native practices had been discarded while promoting foreign ones. These skills were not merely to be used for fitness but they were effectively applied in real combat. The English press reported in the 1930s that Chiang Kai-shek proclaimed that Chinese boxing was to be included as part of all military training, similarly the positive experience as well as the rally of Chinese propaganda after the 1932 Shanghai incident helped promote the creation of Da Dao (Big Knife) teams in different cities for the civilian population.

Wide Training in Big Sword Use is Planned

Students to be enlisted from all nation for Nankin Course

Many already applying to join movement

Nanjing March 24, 1933

People of the whole country will be trained in the use of the “big sword” which has proved its usefulness as weapon against the Japanese, according to a move just started by General Ma Liang, Mohammedan leader of China…

Manuals like Huang Bonian’s Xingyi Fist and Weapon Instruction published in 1928 was used to train in empty hand and armed combat, the sword and bayonet techniques illustrated in this manual differ from the ones shown in Japanese sources (Rovere, 2008). Similarly the Da Dao techniques practiced in the footage that has resurfaced clearly show the variety in how soldiers wielded these weapons whether with a single or two hand grip. Moreover, the Da Dao became a symbol of resistance, on August 1937 Chiang Kai-shek was presented with a Da Dao made of an alloy of gold and silver in appreciation for his leadership. Some authors give little credit to the importance of hand to hand combat during the Second Sino Japanese war, however late scholarship acknowledges this fact. Even though the Japanese had the material resources on the air, land and sea and were skillful in coordinating these branches on the battlefield the Japanese military doctrine “regarded hand-to-hand infantry combat as the culminating point of battle”. A foreign correspondent who was visiting the aftermath of a skirmish between Chinese and Japanese forces wrote that most of the dead soldiers showed evidence of bayonet and sword injuries and few were killed by bullets.

Note: The above picture shows Chinese troops using different weapons such as spears, hook swords, regular Dao, Da Dao and even a Guan Dao

The Chinese on the other hand had limited resources and after the severe losses during the battles of Shanghai and Nanjing in 1937 where up to 70% of the young officers corps were killed, it triggered a change on the Nationalist’ strategy from head on confrontation to guerrilla tactics. The Chinese infantry made use of small arms, machine guns and hand grenades favoring night fighting and hand to hand combat where superior numbers and close fighting could negate Japanese fire power (Peatite, Drea, & Van De Ven, 2011). Chinese forces would seek cover during air and artillery bombardment and wait their opportunity to engage Japanese infantry in close combat. When the war with Japan started Japanese and western observers predicted a quick end of the hostilities with the Japanese as the victor. In spite of severe losses the Chinese did not quit and surprised all doubters, to the point that the learnings from the Chinese war theater were studied with interest by Colin Gubbins father of the British Special Operation Executive (SOE). Gubbins was instrumental in the war preparations to defend Britain against a Nazi invasion where guerrilla tactics could have been employed if needed (Linderman, 2016).

General Tsai Ting-kai, who shows no sign of excitement in spite of the grimness of the battle being waged, say that the casualties suffered have been exceedingly light, thanks to the preparations made beforehand for taking cover from artillery and aerial bombardments.

“Our men” he said, “simply take cover until the roar of the guns has died down and then reappear to meet the attacks of the Japanese soldiers.”

Hong Kong Press, 1932

Conclusion

The push for modernization in Japan and China was critical for the defense of their national interests; even though each country remained loyal to some elements that were deeply ingrained and represented their national essence among these were martial arts. During the Sino-Japanese war, martial arts served as a survival skill specially to the Chinese, given the limited military resources available. In the Japanese case martial arts were a staple of what separated warriors from the layman and a means to instill nationalism by the used of symbols taken from Japan’s proud martial heritage.

Bibliography

Byonghyon, C. (2002). The Book of Corrections Reflections on the National Crisis during the Japanese Invasion of Korea. Berkeley: Institute of East Asian Studies.

Linderman, A. (2016). Rediscovering Irregular Warfare: Colin Gubbins and the Origins of Britain’s Special Operations Executive . University of Oklahoma Press.

Lory, H. (1943). Japan’s Military Masters. New York: Viking Press.

Peatite, M., Drea, E., & Van De Ven, H. (2011). The Battle for China. Stanford: Standford University Press.

Rovere, D. (2008). The xingyi quan of the Chinese army : Huang Bo Nien’s Xingyi fist and weapon instruction. Blue Snake Books.

Yan, B., & Li, R. (2011). Looking Back at the Tianjin China Warriors Society. Journal of Chinese Martial Studies .

4 Comments