By William A. & Mei C.

The Big Knife (Da Dao) is an iconic weapon that even today regularly appears in popular culture outlets such as TV drama series, movies, books, mail stamps, monuments, toys and even graphic novels available for the general public in China. It serves as a stark reminder of national resistance against Japanese aggression in WW2 and an instrument to instill nationalism even in recent years. One of the most comprehensive English treatment on the topic the reader can find on the web is the very informative Kung Fu Tea blog, in this entry we will include additional information we have been gathering in the past few years.

Introduction

The Knife (Dao) is a weapon used by Chinese armies for centuries and refers to blades with a single cutting edge using either one or two hands to wield them. These weapons include short and long pole designs, from blades with a more or less constant width from the guard to the end tip and blades with a increasing width that converges in a sharp point. The conflicts against northern tribes were a source for the introduction of Dao designs into China, similarly during the Tang dynasty some of these blades and probably some techniques to forge them made their way to Japan. Centuries later Japanese blades would become a sought after item by Chinese elites and an inspiration for poetry and other art forms in the mainland.

The earliest illustrated classification of these weapons appear in the Northern Song Dynasty’s (960–1279) “Collection of the Most Important Military Techniques” (Wu Ying Zong Yao, 武經總要) compiled by Zeng Gongliang, this comprehensive manual depicts what scholars define as the apex in cold weapons technology and the moment fire arms development started (Yang, 1992). The material contained in the Wu Ying Zong Yao was compiled and expanded with other extant writings in the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) in Mao Yuanyi’s “Record of Military Preparations” (Wu Bei zhi) . Mao’s work also included material by General Qi Jiguang’s Jixiao Xinshu methods for close quarter fighting and drilling soldiers (Graff & Higham, 2002).

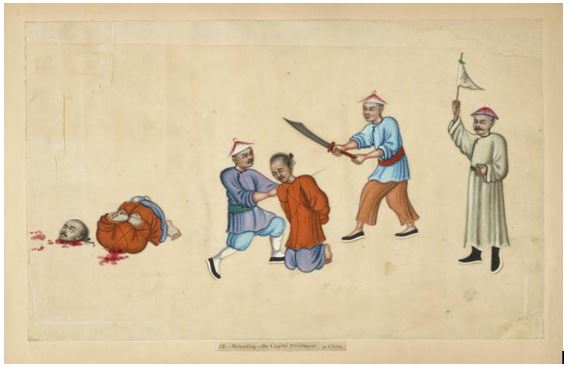

Another source depicting the different styles of Dao is the “Illustrated Standards of Ritual Objects of Our August Dynasty” (Huangchao Liqi Tushi) compiled on imperial order during the Qianlong reign (1711-1799) of the Qing dynasty; the above mentioned treatises are not the only ones depicting the different types of Dao as other encyclopaedias and even novels also contain illustrations of these weapons. During the Qing Dynasty westerners who have settled in China also provided examples of such blades in the form of illustrations and photographs; one of the main themes of these depictions are those of people being decapitated:

The above depiction of the Da Dao as the weapon of choice to punish any challenge to the Qing Dynasty’s authority will continue well after its downfall and the creation of the Republic. Western observers in China provide a glimpse of how the weapon was a source of fear during the dying dynasty. For the foreigners living in the mainland groups like the Da Dao Hui (Big Knife Society) was an unsettling reality too close to home.

“…months ago, a plot was laid to murder Herr Stenz; a group of ruffians broke into the preaching hall at Lichia where a missionary had just passed the day; the bed, which was fortunately empty, was pierced through with spears, the missionary having quitted the place in the twig light. The mandarin of Kiujeh (the same as he in whose district this last crime has been affected) was notified of the occurrence but never took the least notice and it would seem that he approved of the outrage. Equally peculiar has been his conduct in regards to the Society of the “Big Sword;” it was declared that the society had ceased to exist and this finished the matter. This Society is now quietly permitted to grow again, its adherents to hold armed assemblies and to go about as they choose without molestation. Some mandarins go so far as to afford the Society their protection…” NCH 1897

It is easy to understand the angst and frustration from the foreign population given the lack of interest from the Qing government to address the situation. However, for the Chinese the Society was doing what the government could not openly do, to keep western influence and demands in check. The end result of the social unrest was the Boxer Rebellion that contributed to the fall of the dynasty. Unfortunately China would know no peace as foreign influence contributed to the emergence of the warlords and their predations on the population. Some of the societies that formed prior the Boxer Rebellion did not ceased to exist and received a boost as a means to protect peasants against bandits and warlords.

“For the first time, for a great many years, your correspondent a few weeks ago, traveled home by the canal in perfect peace. From every one asked, the answer was all is “tai ping.” Wondering how this state of things had come about, on our return we asked, “Have the soldiers done this?” but the answer was “No, it is the Small Gun Society.” We were told that in the old days there was the “Da Dao-huei” – big knife society. This “small gun society,” like them, professed to be invulnerable to gun shot, and had banded themselves together to defend their homes. Though some have suffered from gunshot, the “tufei” are afraid of them, and certain parts of the country are living in peace.”NCH 1922

Note: “Tufei” refers to bandits

Weapon Design

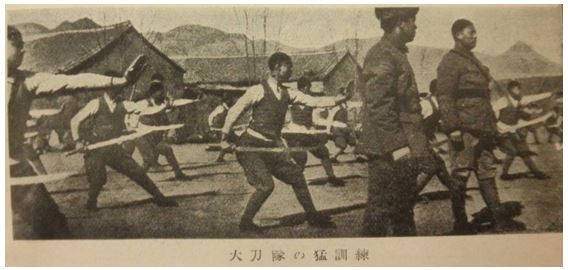

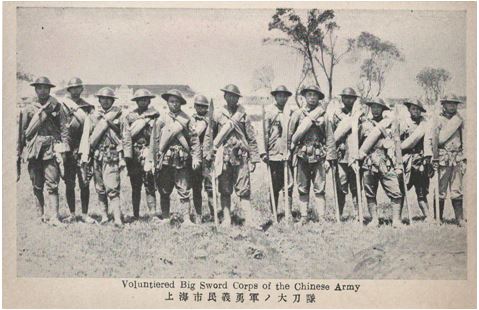

Comparing the above illustrations with other graphic material of soldiers armed with the Da Dao (Big Knife) one can see differences in the style of weapons used on those unfortunate prisoners with the ones during the War of Resistance against the Japanese. In western press releases, Japanese military postcards and Chinese sources the Big Knife (Da Dao) designation is used loosely to lump together almost any bladed weapon shorter than the person wielding it.

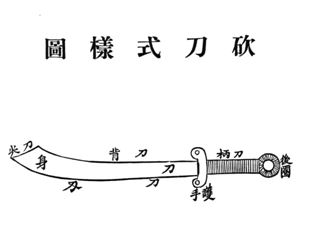

The above examples demonstrate the many variations used when describing what a Big Knife would look like, in 1933 Yin Yu Zhang son of famous Baguazhang master Yin Fu published “Chopping Method Practice”. In the introductory pages Yin Yu Zhang included a description with the dimensions of the Da Dao along with an illustration followed by a short historical background of these weapons.

“The length of the blade is between 23.5 to 25 inches

The cutting blade is two inches wide and an inch and a half wider after twenty-five

The back of the knife is 21 to 25 inches

The point of the knife is in an angle and measures 3 inches wide

The guard that protects the hand is 3.5 inches long and half an inch to one inch thick, ¾ was made out of copper

The handle of the knife is 8.5 inches long wrapped with twisted cotton rope for a firm grab

The end has a ring 3 inch in diameter also wrapped around with cotton rope

The weight is 3.5 pounds

The total length of the knife is 35.5 inches”

There were several designs and not a unique standard model or method for its construction. In general two basic types can be used to classify them: the first one was the Army’s design and the second was by the civilian population. Some of the Da Dao were inherited from previous generations, some came from local blacksmiths and some made at government’s factories. It was common during the Sino Japanese conflict that civilians would donate money for the construction of Da Dao and then provided to the army. The Army’s Da Dao (Jun Yong Da Dao) resemble the design in Yin’s manual, surviving samples have on average a total length of eighty five to ninety centimeters (33.5 to 35 inches); the blade length was sixty centimeters long (23inches). The weight oscillated between 1.2 to 1.5 kilograms (2.65 to 3.3 pounds). The back of the blade was thicker than the cutting edge; the Dao’s end was wider than the base. The weapons made at the government’s factories were for the most part of better quality than the ones made by local blacksmiths. Government factories used better quality steel for their construction, while local smiths used any scrap metal available (including sabotaged railways by Chinese guerrillas) with variations in the weapons measurements. The factory weapons had guards made of iron or copper with one loop on either side, with a ring at the pommel and the grip was fitted with two pieces of wood and wrapped with cotton (Jiang, 2007). The ring at the pommel can be traced to much older weapons throughout China’s history. Other designs had round and “S” shape guards with variations in blade dimensions. Modern replicas made by Cold Steel and Hanwei are heavier and with not very good balance, when visiting professor Ma Lianzhen I was able to hold a custom made Hanwei Da Dao with proper weight distribution and balance when wielding it on one hand.

Republican China

As Chinese political and social unrest continue the Japanese saw it as an opportunity to increase their sphere of influence in Asia and after the victory in the Russo – Japanese War further strives were taken to secure Japanese claims in the region by invading Manchuria in 1931. Japanese invasion in the north along with instigated anti Japanese sentiment triggered further civil unrest in cities like Shanghai that led to an incident in 1932. Armed conflict between the two countries was not escalated as both sides were buying time to better prepare themselves and in the case of the Nationalist Chinese government to annihilate the communist. In an article titled “Discussing the National Arts“, published in the National Arts Weekly Magazine (Guo Shu Zhou Kan) 1934, it describes the importance of the Big Knife (Da Dao) during the 1932 Shanghai’s January 28 Incident (Yi Erba Song Hu) where the Chinese soldiers used these skills in close quarter fighting against the Japanese troops. A similar statement appeared in Yin Yu Zhang’s manual.

“Definite plans have been made to send important Chinese reinforcements to the Shanghai area to assist the gallant 19th Route Army.

General Chiang Kai-shek, former generalissimo, held a lengthy conference after his arrival here to-day with Mr. Lo Wen-kan, Foreign Minister and General Ho Ying-sching, his former chief of staff, in his residence in the Sun Yat-sen mausoleum park, concerning the situation in Shangahi.

General Chiang proceeded with Madam Chiang to Tongshan hot springs this afternoon, where a further conference will be held tonight.

Pukow was the scene to-day of busy military activities. The 54th division, under the command of General Shangkuan Yun-hsiang, together with General Feng Yu-hsiang’s “Big Sword Corps,” which created so much difficulty for General Chiang’s crack troops in the war of 1930 in Honan, are being “loaded” on trains preparatory to being transported to Shanghai to assist the defense forces there. – United Press” NCH February 16, 1932

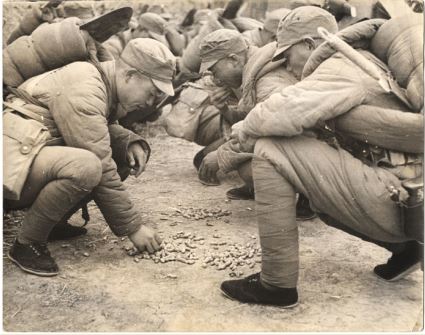

The techniques using the Big Knife were performed either with a single or double hand grip, footage of soldiers training with these weapons show the variety of methods used. This is not surprising given that many different martial arts instructors with different backgrounds taught fighting techniques to the Big Knife teams during the war. After the Shanghai incident an initiative to train civilians in the use of the Da Dao was initiated, this included demonstrations in different cities. Even though the usefulness of such weapons in modern warfare was limited it did contribute to the mental and physical preparation of the population at large.

“Wide Training In Big Sword Use Is Planned

Students To Be Enlisted From All Nation For Nanking Course

Many Already Applying To Join Movement

Nanking, March 23 – (Special)

People of the whole country will be trained in the use of the “big sword” which has proven its usefulness as weapon against the Japanese, according to a move just started by General Ma Liang, Mohammedan leader of China.

The move aims at the organization of a “National Big Swords Army” to begin at Nanking. The idea of the Mohammedan leader has met with enthusiastic response has met with enthusiastic response s scores of young Chinese have registered their names with the Central Boxing and Swordsmanship Training Bureau asking to be members of the Big Swords Army under organization.

According to a scheme laid down by General Ma, Nanking will be divided into eight districts, each to have one company of the Big Swords Corps. All who join the organization will be required to undergo boxing training in the Central Boxing and Swordsmanship Training Bureau before being taught the use of the big swords.

The organization of the Big Swords Corps will gradually spread to all cities and the countrysides throughout the nation until people of the whole country are equipped with and thoroughly trained in the use of the big sword as an effective weapon.” The China Press 24 Mar 1933

As a follow up of the above announcement the business community rallied to answer the call. On May 20, 1933 the English press reported that the Greater Shanghai General Chamber of Commerce collected 800 big swords in support of the big sword corps. It is interesting to note how contradictory Ma Liang’s political acumen was when supporting this initiative given the fact that he demanded the locals to embrace Japanese enterprise in China by threat of force back in 1919. Despite the national call to protect the nation, the 1933 student rallies organized to profess their love for the country were harshly put down by the government using Big Swords units and police with the pretext that Communist had infiltrated the demonstrations. This heavy handed approach did not escape critics from the students and even the forces sent against them.

“One student thus attached by the police fell near where this correspondent was standing. About six Paoantui jumped on him and began beating him with the dull edge of their heavy swords and kicking him, shouting “if you want a demonstration we’ll give you one!”. The student made no effort to resist, but cried out: “Beat me! Kill me if you wish! I am a Chinese who loves his country!” The China Press 1935

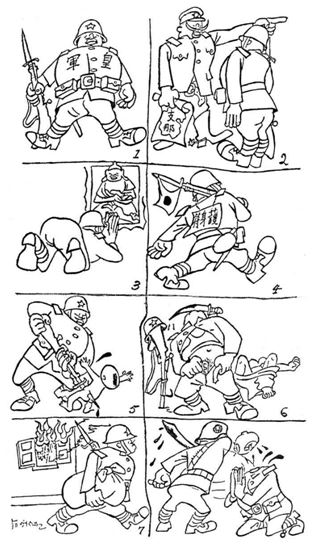

Chinese Political Cartoons (Manhua)

Lithographic illustrations became popular at the end of the 19th century followed by illustrated story (lianhua) and comics books. The Dianshizhai Pictorial that appeared in 1880s became very popular and was followed by other publications that reproduced images from classical novels like the Story of the Three Kingdoms with the appearance of the publishing industry these books as well as commercial advertisement flourished. Following the example of Japanese Manga, Chinese illustrators gave way to an industry shaped by the social events of the time. (Shen, 2001). While the work produced before the Japanese war was centered on entertaining, commercial and satire once the war started the artist circles believed that their trade had to serve a better purpose and rally the nation leading to the creation of Resistance Cartoons propaganda (Kangzhan Manhua). These artists created the Cartoon Propaganda Corps (Jiuwang manhua xuanchuan dui) in 1938 active until 1940 with some interruptions in their work (Pozzi, 2014). While both the Nationalist government and the communist made use of this tool to further their agendas, it was the latter that was the most successful.

Despite the volume of work created, these intellectuals published their cartoons mainly in major centers and in many cases their message included in the illustrations was not clearly transmitted to those outside educated circles and for these reasons the population in rural centers were partially exposed to it if at all. After the Cartoon Corps was disbanded many of its members joined the communist and traveled to the country side to continue the propaganda work against the Japanese. In the occupied areas the Japanese also made use of propaganda cartoons to gain support from the local population. The male Chinese cartoonists used depictions of women and children being raped and killed by the invaders to inspire rage and will to resist, while using women’s bodies as victims Chinese soldiers depictions were different in order to instill morale. Soldiers depictions are mostly of them fighting back or in the worst of cases injured (Pozzi, 2014). Many of these images have the Da Dao as the tool use to exert justice, it symbolized a warrior past and that even if the Chinese army did not have the same resources as its antagonist one could still fight back even if a Da Dao was the only weapon available.

Three Hairs

Chinese children and adults of today are still very familiar with one of the most famous strips that appeared in 1935 and ran until 1962. The brain child of cartoonist Zhang Leping (1910 – 1992) broke away from the norm by choosing a child as his hero. This cartoon depicts the misadventures of orphan Sanmao (Three Hairs) while trying to survive in the streets of the big city and later the Sino Japanese conflict. The situations Sanmao endures are quiet disturbing in many cases even for adult readers. Zhang Leping did not pull any punches illustrating the hardships caused by poverty, social injustice, corruption and war on the less fortunate specially children. As war rage on some of the stories depict Sanmao rallying both young and old to take an active part in the defense of the country. After the communist take over the CCP would re shape Sanmao’s character to match the ideological and historical message the party wanted to transmit to the masses. Even though it was not common practice to recruit children there were instances when both actors of the conflict included youth in their ranks.

The Dao Dao March

After the 1937 events at the Marco Polo Bridge when Song Zheyuan’s 29th army faced the Japanese onslaught, 23 year old Mai Xin composed a song to honor the sacrifice of the men who died in that battle and to instill a will to fight the Japanese. Sadly after facing the brunt of Japanese military might the Chinese forces were decimated and the Japanese took control of Beijing and continue their push south.

“The Da Dao cuts the heads off the devils

The brothers of the 29th army

The war against the Japanese has arrived

Before you are the Northwest army

Behind the citizens of our nation

Our 29th army is not alone

Attack the enemy and destroy it!

Destroy it!

Attack!

The Da Dao cuts the heads off the devils

Attack! (Acevedo & Cheung, 2009)

Modern Day China

Even though seventy two years have passed since the end of the Japanese conflict reminders of the invasion are very much present in everyday lives. The rise of revisionism, right wing parties in Japan and the CCP’s use of memories of the conflict to divert public opinion and avoid criticism at home has helped make popular TV series and movies based on the war (in the last couple years the popularity of these kind of dramas has dwindle) where the Da Dao teams are the central protagonists. Similarly other artistic endeavours have the Da Dao as inspiration e.g. sculptures, paintings, theater, comic books and even toys as illustrated below. There is a dark side to the above; the Chinese government has very strict regulations around the ownership of fire arms leading to the use of cold weapons like the Da Dao by criminal gangs to commit their crimes.

Conclusions

The Da Dao is a weapon that was used by Chinese military/militias units during the Sino Japanese war due to the insufficient access to modern weaponry. The Da Dao design varied and included elements from China’s past linking the warriors of old to the modern soldier. As a symbol it was used both as a tool for government control as well as inspiration to resist the invaders; it has continue to play a lesser role to remind citizens of the crimes committed in the past by the Japanese with the goal to instill nationalism at home.

Bibliography

Acevedo, W., & Cheung, M. (2009). Las artes marciales del ejército chino en el Periodo Republicano. Revista de Artes Marciales Asiáticas .

Graff, D. A., & Higham, R. (2002). A Military History of China. Cambrigde: Westview Press.

Jiang, H. (2007). Zhongguo dao jian. Jinan: Ming tian chu ban she.

Pozzi, L. (2014). “Chinese Children Rise Up!”: Representations of Children in the Work of the Cartoon Propaganda Corps during the Second Sino-Japanese War. Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review .

Shen, K. (2001). Lianhuanhua and Manhua–Picture Books and Comics in Old Shanghai. University of California.

Yang, H. (1992). Weapons in Ancient China. NY: Science Press.

4 Comments