Credits to Mei C. for correcting my draft translation and Azusa M. for her help with the Japanese text.

After a hiatus to take care of my new baby girl and a holiday to the Rockies I got the itch to write again. A post in the Kung Fu Tea: Martial Arts History, Wing Chun and Chinese Martial Studies Facebook page reminded me of a topic I have read in the past, which also ties with my own research on the influence of the Japanese crisis during the Ming dynasty development of Chinese martial arts. Depictions of the scroll so far shown on the web are only partial and of poor resolution, it was a good challenge to try and find better quality pictures to share with my readers. After a day’s effort I located the complete scroll in HD.

Introduction

The original scroll is currently held at the Tokyo Daigaku, Shiryo Hensango [Institute of History, University of Tokyo] and one reproduction is located at the University of Princeton (Pirates of the Eas China Sea, 2014). The original’s dimensions are 32x523cm. The title of this work of art is Ming Qiu Shizhou Taiwan Zoukai Tu (Victory in Taiwan by Qiu Ying [pseudonym Shizhou] of the Ming, 1494 – 1552). Scholars argue that the scroll does not match Qiu’s style and period, rather another painter created this work emulating Qiu’s style (Pirates of the Eas China Sea, 2014). It is important to point out that these scrolls, unlike western paintings, are not meant to be on constant display revealing the painting from right to left; rather the owner will store it away until the time to “immerse oneself into the world of the painting” (The New York Times, 2014). As the scroll is unrolled one will encounter seals of ownership, followed by the painting itself. At the very end of it, the scrolls can reveal more seals, along with commentaries by other scholars about the work of art. These master pieces have a sense of distance and space that is revealed as one slowly uncovers the work, while absorbing every detail before moving on to another scene (The New York Times, 2014).

The Pirate Crisis

The Chinese called them using the derogatory “dwarf invader” (wokou, 倭寇), in Japanese (wako, わこう) and Korean (waegul, 왜구). These bandits were an international problem for the three countries, starting as early as 1223 when a Japanese pillage expedition travel to Korea probably due to famine and social unrest (Hazard, 1967). Some Asian scholars divide the first incursions “early wako” (14th century) from the “late wako” (16th century). Early expeditions were more of a nuisance when compared with the later waves that required the Ming government to act upon them with force, by the 16th century these pirates had a greater degree of sophistication in their tactics when compared with the 14th century “trials”. The Ming protectionist trade approach only help to exacerbate an ongoing problem, the Chinese court’s trade was exclusively through their approved embassies and missions. It was a matter of time when this strategy would trigger smuggling and contraband (Pirates of the Eas China Sea, 2014). By cracking down on the illegal trade, those bold enough to defy the Ming court grew into bigger, more aggressive groups that included not only Japanese, but also Chinese and others who wanted a piece of the lucrative action; one could say that this was a matter of economics, for as long as the benefits of looting outweighed the risks it was a good endeavour to pursue. Years of war in Japan served to create veterans that were not easy to deal with in the battlefield by the regular Chinese forces. One glaring example of such challenges to Chinese authority is what the Japanese call the “Military Expedition Miracle” (in transliteration Jun Shi Qiji Di Zheng Cheng). The History of the Ming Dynasty’s (Ming Shi) account of this event is as follows (comments and translations are my own):

“A time of extreme sorrow spread from Jiangsu to Zhejiang, everything was ravaged. The new dwarfs [wo, 倭] arrived taking advantage and profiting from the crowds, fiercely unrestrained. Disembarking from their boats to go ashore and plunder.

From Hangzhou [sub provincial and capital of today’s Zhejiang province] to the north to rob in Chunan [a county in Hangzhou], moving quickly to Huizhou [a district of today’s Huangshan city], from Shexian, arriving to Jixi [county in Xuancheng, Anhui], to Jingde, crossing to Jingxian, hastening to Nanling [county in Wuhu, Anhui], succeeding to reach Wuhu [prefecture level city in Anhui].

Burning Nanan [Southern shore], hurrying to the seat of government, violating and subduing Jiangning [a district of Nanjing city in Jiangsu], directly invading Nanjing.

The dwarfs have their clothes covered in red and wearing yellow hats, commanding many to assault the virtue of countless homes, pressing from either side, fast approaching the hills, leaving the river to plunder Liyang [county level city in Changzhou, Jaingsu], Yixing [county level city in Wuxi, Jiangsu].

Hearing the news, the officers and their men from Tai Hu [Lake Tai near Wuxi city, bordering Jiangsu and Zhejiang] came out reaching Wujin [district of Changzhou city, Jiangsu], supporting Wuxi to stationed in Huishan.

In one zhou ye [24 hours period], to rush hundreds towards eighty li [a li corresponds to 500 meters in modern terms] pressing to the villa in the bank of the river; one hundred eighty li.

Because of the government’s army they encircled after chasing in a forest bridge to annihilate them. The dwarfs were surrounded by the government’s army, followed them to Yang Lin Bridge and finally defeated them.

The whole battle, there were no more than sixty or seventy dwarfs, but had the power to swapped thru thousands, murdered more than four thousand people. From the moment they arrived to shore to their defeat lasted about eighty days. This happened during the thirty four year of the ninth month of the lunar year [September, 1555] during the Ming dynasty [Jiajing Emperor’s reign 1521-1567]” (Ming Shi)

This account reveals how unprepared the Chinese forces were to control the situation, the obvious organization of the wokou to accomplish such feat and the fear they struck on their victims during this episode. Chinese scholars point out how cruel these men were, an eerie reminder of things that would come to pass decades and centuries later both in China and Korea during the Imjin (1592 – 1598) and the Second Sino Japanese (1937 – 1945) wars. The following year, 1556, a young Chinese commander was transferred to the south to support the Chinese government’s pacification campaign against the pirates, his name was Qi Jiguang (Goodrich & Chaoying, 1976). The reader is encouraged to visit my YouTube Channel to watch a Discovery Channel documentary that aired in 2008.

The Scroll

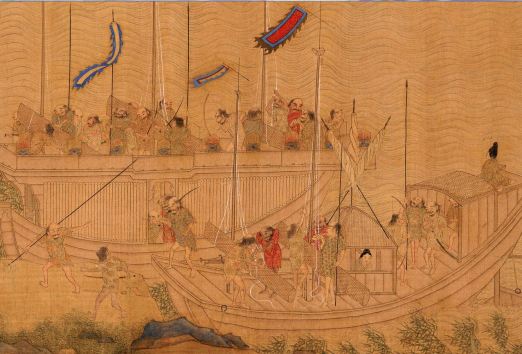

I will only point out a few details I find interesting, but will encourage the reader to do the same and comment to enrich the discussion. The first thing we see as we move to the left is some far distance boats as they travel to shore, setting the stage for what it will be revealed next. A somewhat peaceful scene, yet knowing what the scroll is all about, it kind of sets the stage for the storm to come.

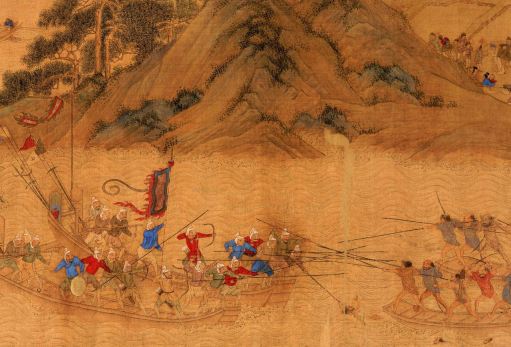

The first boats that come to the beach, show the pirates preparing their weapons and gear e.g. long spears, bow and arrows and their feared sabers. In this scene we observe two women, perhaps wives/concubines of the chiefs. One the pirates on deck blows a sea shell.

Another character already on land wears armor, and some type of shorts as the other bandits, perhaps master less Samurai/Ronin push forward. Skipping ahead there is at least a pirate armed with what appears to be a matchlock. The earliest introduction of the matchlock to Japan was around 1543.

Then as some pirates move ahead looking to loot, others are already returning with their bounty as the inhabitants of the town are leaving in fear.

After the scene of destruction and chaos, we finally witness the arrival of the “cavalry” as Chinese troops battle the pirates on boats. The Chinese are armed with spears, bow and arrows, some have double dao (knive), the troops crossing the bridge seem to have straight swords, shields, dao with long staff ( Zhanmadao) etc. It is here that I wonder how accurate is the portrayal of the Chinese troops weaponry. We know that some of the troops used to meet the pirates were trained on Qi Jiguang’s tactics (which proved very useful even during the Imjin War); yet I don’t see the Wolf Tooth Spear (langxian) or the Mandarin Duck Formations (Yuan Yang Zhen) used successfully in these battles, some of the weapons don’t appear in the Wu Bei Zhi (Military Records) by Mao Yuanyi either.

The painting ends with a depiction of Chinese troops as they leave their stronghold to do battle. The inscription on top of the gate reads 海防新堡 (Hai Fang Xin Bao, Harbour Defence New Fortress).

To complement the earlier version of this post in the original’s title there is a mention of a victory in Taiwan, however this do not match the dates in which the first arrivals to the island landed (Portuguese survivors of a ship wreck in 1582), Dutch foreign settlements dated 1623. The Chinese under Koxinga would not take over until 1661.

The matchlock also gives a clue of a later than a 1543 origin. Qi’s troop training did not started until 1557, the Ji Xiao Xinshu manual was first publish around 1560. Additionally the worsening of the pirates incursions took place after 1552 when Tan Lun, a Ming officer was transferred south to take charge of coastal defense against the pirates. All of the above suggest that the author of the painting is not Qiu Ying (1494 – 1552) and that the mention of the island of Taiwan in the title is not correct. I hope this short essay opens up new research options to the reader, I’d encourage you to keep me posted on it.

Bibliography

Goodrich, L. C., & Chaoying, F. (1976). Dictionary of Ming Biography. Columbia University Press.

Hazard, B. H. (1967). The Formative Years of the Wako. Monument Niponica, 260-277.

Ming Shi. (n.d.). Juan 322, 17.

Pirates of the Eas China Sea. (2014, 08 08). Retrieved from Marquand Library of Art and Archeology: http://marquand.princeton.edu/highlight/6409644

The New York Times. (2014, 08 08). Retrieved from Arts: Ancient Chinese Art : http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WPmED0GbYUs

Compare dates of painter with dates of General Qi and you may see why there is a discrepancy between the weapons and formation of General Qi and those presented in the scroll. You might also want to consider the role that abstraction plays in Chinese painting and and composition as well as the subtle symbolism in the work in analysing the piece as a narrative.

The depiction of this scroll is accurate, AFAIK. Qi Ji Guang was not the only general to combat Wokou, and not all Ming armies were modeled after his troops.

I would like to inform you that there’s a “sister” scroll of sort, in worse preserved state, currently in China. The sister scroll is (probably) painted by another painter, but depicts Ming troops in exactly the same gear as this scroll.

Oh, the “Dao on long shaft” is known as Zhanmadao.

Good points, thanks for the insight